Blog summary:

- Many real-world problems require balancing competing objectives—like cost vs. quality or risk vs. return.

- Classical computers often struggle to capture the full picture of these trade-offs.

- A new quantum algorithm could soon unlock smarter decision-making in industries like finance and logistics.

Researchers have long suggested that quantum computers may one day solve valuable optimization problems beyond purely classical methods. These problems are everywhere. They shape financial markets, power energy grids, and even govern the mobile apps that route your journey home and deliver your dinner. But which optimization problems truly demand quantum methods? Where can quantum computing make a real impact beyond classical solvers?

The latest paper from the Quantum Optimization Working Group, recently published on the cover of Nature Computational Science, offers an intriguing new path for exploration. It introduces quantum approximate multi-objective optimization (QAMOO), a novel algorithm that builds on the well-known quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA), adapting it for complex problems where we must balance multiple competing objectives. The authors—comprising researchers from Zuse Institute Berlin, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and IBM—say the QAMOO method could have enormous relevance across industry and science, and that it represents one of the most promising proposals for near-term quantum advantage in the field of combinatorial optimization.

Combinatorial optimization is all about finding the best possible choice out of a discrete set of feasible options. These problems are notoriously challenging for classical computing methods, especially when they involve vast sets of possible solutions or when solutions must satisfy complex constraints.

Despite these difficulties, the optimization community has developed many powerful classical algorithms that provide “good enough” solutions to many real-world optimization problems. This raises the bar for quantum optimization. To become industry-relevant, quantum methods must deliver breakthroughs for valuable, real-world problems where classical methods fail.

That’s where multi-objective optimization enters the picture. This class of problems stands out as a potential “sweet spot” in the search for quantum advantage in optimization. It requires computational problem solving that is not only practically relevant and algorithmically difficult, but which is also well-suited for exploration with quantum computational methods.

More study and classical benchmarking are needed, but early results show that QAMOO may soon outperform classical methods under certain conditions.

The challenge of multi-objective optimization

Today’s classical computing methods are often very effective when it comes to tackling single-objective optimization problems, where we aim to analyze a set of possible solutions and identify the best option for meeting a single objective. In finance, we might say: “build a portfolio of investments that maximizes expected returns.”

Solving the truly single-objective version of this problem means either ignoring factors like risk, liquidity, transaction costs, and regulatory requirements—which would likely make the problem meaningless for real-world use cases—or it means setting pre-defined targets for these factors that we treat as the optimization problem’s constraints.

A simple example of this latter approach might be: “build a portfolio of investments that maximizes expected returns without exceeding a certain level of risk.” Without multiple objectives, the problem is easier to solve, but real-world optimization problems are rarely so simple.

Multi-objective optimization problems are much more complex, and often more representative of the real-world problems we face every day. Instead of a single solution to meet a single objective, they require a diverse set of solutions that represent the various tradeoffs among conflicting goals. When we identify the set of solutions where, in each case, no single objective can be improved without making at least one other objective worse, we have identified what’s known as the Pareto front—the full set of optimal tradeoffs among competing objectives.

Mathematically, all solutions on the Pareto front are equally valid. It’s a bit like an investment manager offering clients different levels of expected returns depending on the amount of risk that they’re willing to accept. Choosing the best option comes down to a decision maker’s preferences and priorities.

It’s easy to see why multi-objective problems are so computationally challenging. Classical methods have a hard enough time exploring the combinatorial solution space for just one objective. Each time we add another objective, like minimizing risk or diversifying assets across sectors, we introduce a new dimension of complexity.

With multiple objectives, the number of potential solutions remains the same, but we can no longer say there is some single-best solution that is objectively better than all others. Instead, we introduce a potentially very large solution set made up of solutions that are all optimal in different ways—the Pareto front.

In practice, classical optimization experts often simplify multi-objective problems by converting them into single-objective formulations with constraints. This approach is more manageable for classical methods, but it forces practitioners to make choices often based on their intuition and general expertise, meaning they may miss opportunities for better tradeoffs.

Let’s say we focus our portfolio optimization effort on minimizing risk. We can take our other competing objective of maximizing investment returns and reformulate it as a constraint—deciding arbitrarily that we will target a return rate of 5%.

This is a more manageable problem, but how do we know we’re not missing out on something better? Could settling for a negligible drop to a 4.9% return rate lead to a solution with vastly lower risk? It’s possible, but a single-objective formulation doesn’t give us the flexibility to explore that potential.

In practice, there are many classical methods that could solve this as a two-objective optimization problem. However, if we add additional objectives beyond that, the problem quickly grows too complex for classical methods.

Capturing the full Pareto front allows us to make more informed decisions and achieve better outcomes, but doing so efficiently poses a challenge for classical-only methods. Optimization researchers have developed methods that can solve problems with a small number of objectives, say two or three, but computational difficulty rises sharply as the number of objectives increases, and quickly grows to be entirely out of reach for purely classical techniques.

Sampling: A quantum computer’s superpower

Quantum computers are adept at exploring large solution spaces because they are, at their core, sampling machines that can return many different solutions quickly. To extract information from quantum computers, we must perform measurements. We measure each qubit used in the quantum circuit, and those zeroes and ones form the bit string that represents the circuit’s output or “sample.”

When it comes to quantum simulation problems where, for example, we might want to calculate expectation values for observables in quantum systems, those individual samples aren’t useful on their own. We might need to perform a million measurements and aggregate all that data to get one useful estimate of an expectation value. However, for optimization problems, each bit string we sample represents a potential solution to our optimization problem. That means each output is a useful piece of information that may yield valuable insights.

This property makes sampling a compelling approach for multi-objective optimization problems. With these problems, our goal is not to find one perfect solution; it’s to generate a diverse set of good solutions that span the various trade-offs. QAOA delivers this diversity naturally, and sampling applications often have a much lower overhead for mitigating the impact of hardware noise when compared to circuits that require precise expectation values.

For more details, refer to our previous optimization blog, as well as this 2024 paper exploring the impact of noise on quantum sampling applications.

Sampling is the most basic operation a quantum computer can do. All other quantum applications are ultimately derived from it. This means quantum computers are well-suited to tasks that require fast sampling and have a tolerance for approximate answers. In multi-objective optimization, that is exactly what we want.

The QAMOO algorithm

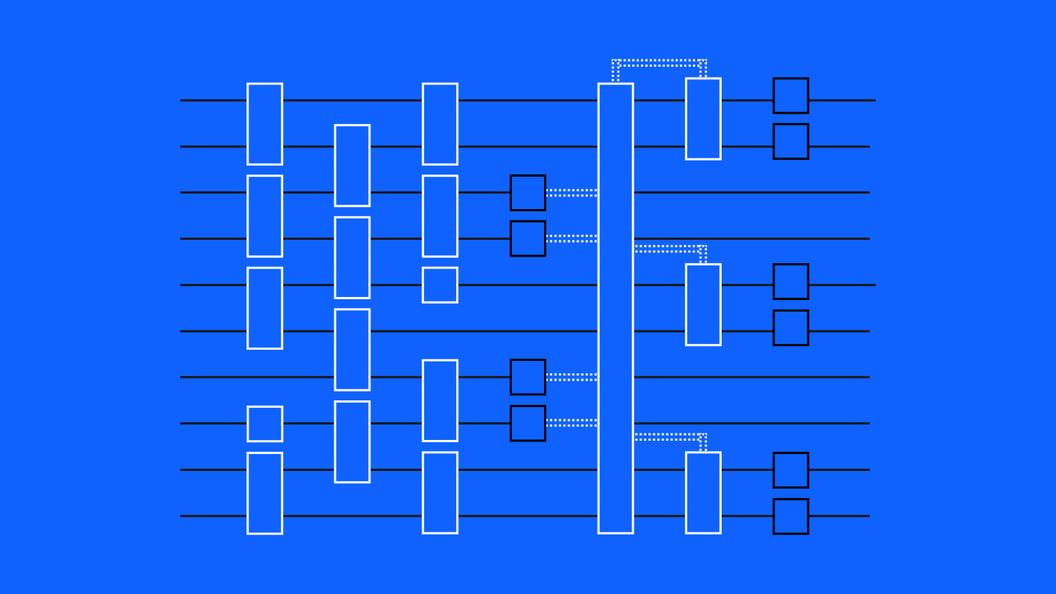

To solve a multi-objective optimization problem, the QAMOO algorithm begins by converting the problem’s objectives into separate unconstrained binary optimization problems, a type of optimization problem that we can formulate as an expression over binary variables—0 or 1—with all constraints folded into the objectives. This transforms the problem into a multi-objective unconstrained binary optimization problem we can approach with quantum computation.

Unconstrained binary optimization problems are studied widely in quantum optimization because they map naturally to both classical optimization solvers and quantum optimization algorithms like QAOA (quantum approximate optimization algorithm). In the QAMOO paper, we specifically use a “quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO). However, recent research explores the applicability of the QAOA to high-order problems, and the methods in the multi-objective optimization work could also apply to high-order problems.

From there, QAMOO defines a single-objective QAOA circuit using a parametrized weighted sum of the original objectives. In other words, the algorithm essentially merges all objectives into a single value, each one weighted by an adjustable parameter that will later represent the importance of the individual objective relative to all the others.

This process converts the multi-objective problem into a parametrized family of single-objective problems that we can tackle with QAOA. The circuit parameters are then optimized just once on a representative instance of the weighted combination of objectives.

In our study, we were able to generate a representative training instance that was smaller than the full-scale problem, and chose to optimize the parameters using classical computing. Classical computers can be much faster and more reliable than quantum computers for parameter optimization tasks—at least when circuits are relatively simple.

That’s because training a quantum circuit often is simpler than sampling from it, since it’s easier to approximate. It’s also possible to train parameters on small-scale instances and transfer them to larger ones as long as they are of a similar type. This makes the workflow of classical parameter training followed by quantum sampling a useful pattern even at larger problem scales.

Once the optimized parameters are set, QAMOO applies them to many different weight combinations, each representing a different balance among the original objectives to enable efficient exploration of trade-offs. Each set of weights creates a new version of the combined objective, and the pre-trained QAOA circuit samples solutions from each one.

This approach makes it easy to explore many different trade-offs without retraining the circuit for every weighting. Together, these sampled solutions form an approximation of the Pareto front. Instead of delivering just one good answer, QAMOO offers a menu of high-quality solutions. Decision makers can then evaluate the full picture before choosing the option that best suits their needs.

In the QAMOO paper, we evaluate the algorithm on multi-objective versions of Max-Cut, a widely studied optimization problem, using both IBM Quantum hardware and a classical simulator. The results show that quantum simulations achieve a higher solution quality faster than traditional classical methods. Executions on real hardware followed a similar trend, though the algorithm was slowed down a bit by device noise.

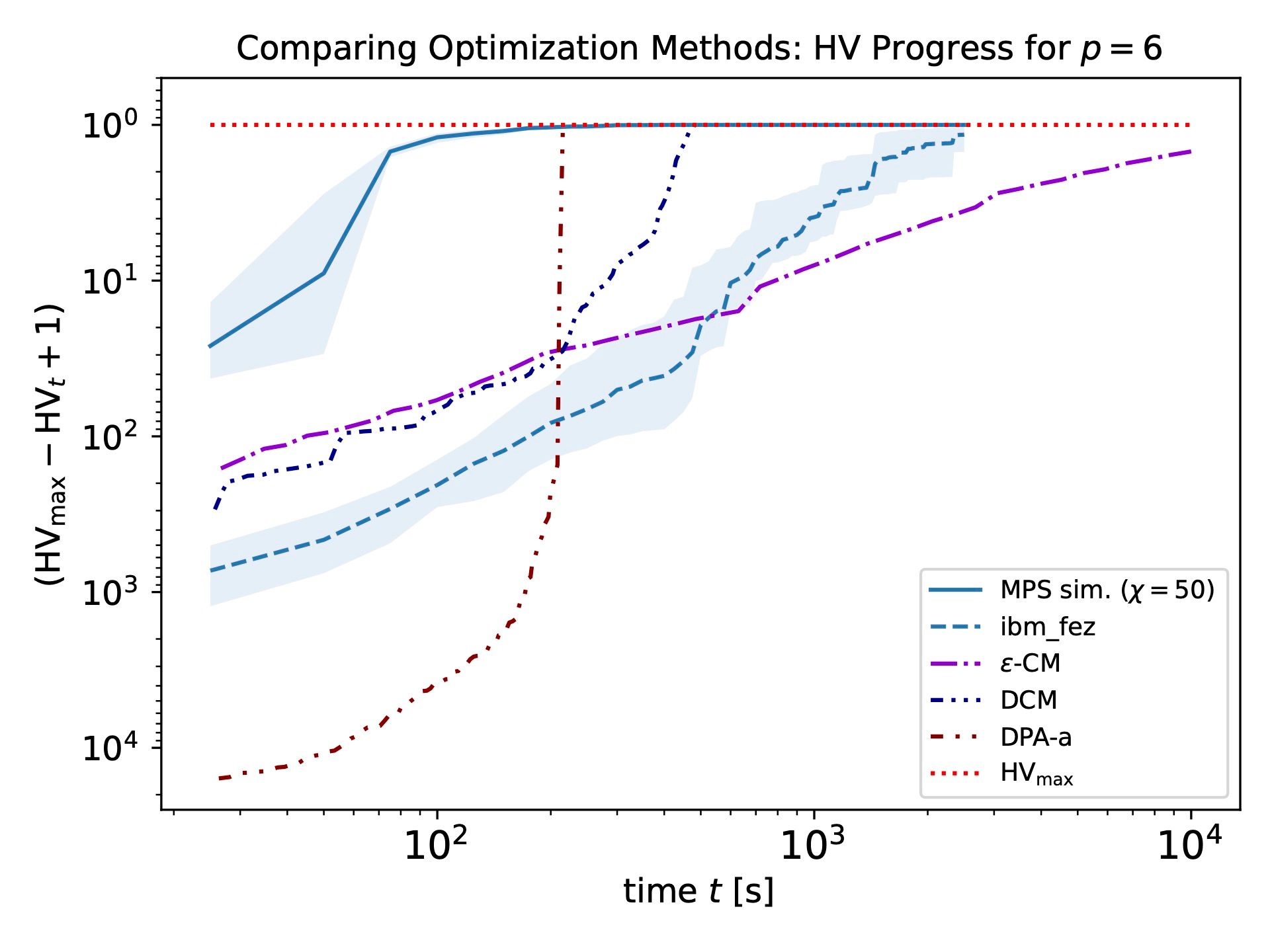

You can see a comparison of results from classical simulations of the QAMOO method, real quantum hardware runs, and a selection of popular classical optimization solvers in the figure below. The figure shows how each method performed in solving a Multi-Objective Max-Cut optimization problem. In particular, it shows the results of QAMOO executions using QAOA circuits with six layers of operations (p = 6)—the deepest circuits tested for the QAMOO paper:

The dotted red line at the top of the figure represents the best-known solution to the problem, i.e. it represents the maximum possible hypervolume (HV)—a measure of how well a set of solutions approximates the Pareto front. The solid blue line represents the classical simulation of the QAMOO algorithm, the dashed blue line (ibm_fez) represents the quantum hardware runs, and all dotted-dashed lines represent different classical solvers.

Taken altogether, the figure shows that simulated QAMOO runs reached the optimal solution faster than classical solvers, one of which failed entirely at reaching the optimal solution in the given time. The QAMOO algorithm also reached the optimal solution when run on real quantum hardware, and we expect that its performance on quantum hardware will improve substantially as quantum computers continue to mature and error rates decrease.

Charting the course to quantum advantage in optimization

The Quantum Optimization Working Group sees QAMOO as an exciting candidate for near-term quantum advantage in optimization. Continued improvements in quantum hardware will amplify its benefits—enabling deeper, more complex circuits that better represent the nuanced tradeoffs between competing objectives.

In the long-term, the QAMOO algorithm could have enormous relevance and deliver tremendous value for use cases ranging from finance and logistics to healthcare and consumer technology. Whether you’re a multi-billion dollar enterprise organization, or someone trying to find the fastest route home with the fewest tolls, we all face multi-objective optimization problems. Access to a tool that delivers a diverse selection of good solutions could bring fundamental shifts to how we explore trade-offs before committing to target goals.

However, to realize this future, we’ll need to conduct extensive, rigorous testing that pits the QAMOO algorithm against the most powerful, sophisticated, cutting-edge classical optimization methods available. We need classical algorithms researchers to try their very best to outperform the QAMOO method with purely classical techniques. This friendly competition between quantum and classical methods will be essential as we journey towards the first demonstrations of quantum advantage in optimization.