Prior to the mid-20th century, computers were purpose-built, room-sized assemblages of vacuum tubes. They were designed with well-defined problems in mind, like tabulating and performing complex calculations. Realizing their full potential took more than improving hardware, though. It required creative minds devising new algorithms.

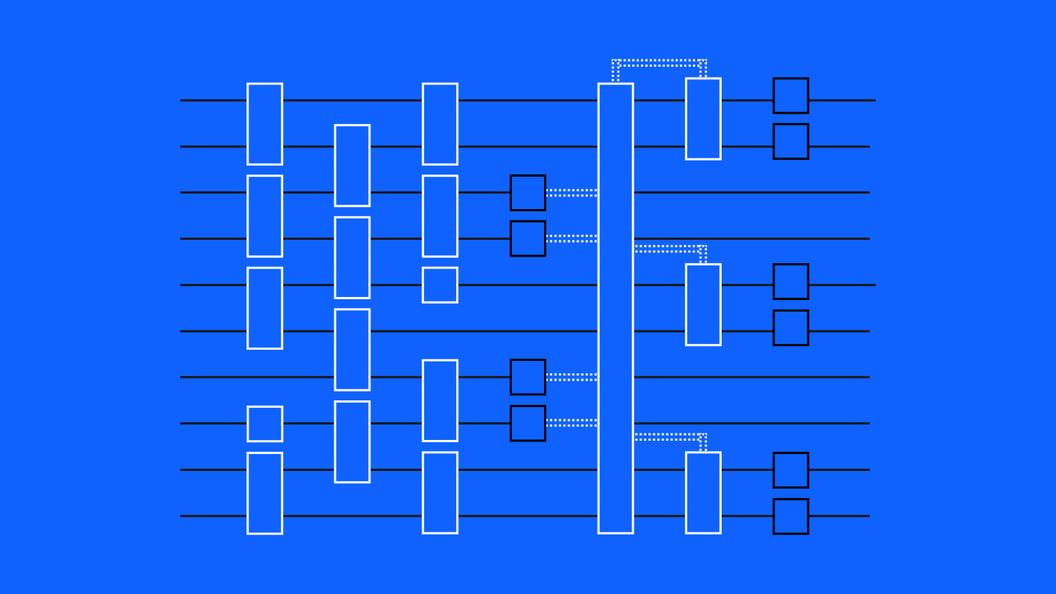

Quantum computing is in a similar boat today. Quantum hardware has matured such that today’s nascent systems can begin solving problems, and the industry has crafted detailed plans to miniaturize and scale. While certain quantum algorithms promise speedups for problems in chemistry simulation, materials science and optimization, quantum algorithm researchers remain on a lookout for quantum algorithms with transformative applications, in much the same way algorithms like hashing and fast Fourier transforms transformed classical computing prior.

Recently, theorists at IBM Research have uncovered a new quantum algorithm demonstrating a substantial speedup over the best classical methods. It exploits a profound connection between quantum physics and mathematics—and provides inroads toward answering long-open questions in the latter field. It also dusts off an old quantum algorithm that had previously been written off.

Where this new algorithm will be deployed remains to be seen. For now, it’s a template for quantum speedup that could be used to develop quantum algorithms, though the analysis of the potential speedup also calls for further scrutiny. Regardless, it demonstrates the kind of creativity that will turn quantum into a transformative compute paradigm.

“This work establishes a path to look for quantum speedups” said Vojtěch Havlíček, one of the researchers behind the new algorithm. “I hope it will help us develop new quantum algorithms.”

Fundamental symmetries and representations

Nature has structure. Planets, people, and atoms all follow a set of mathematical rules which govern that structure—the ways they must behave, the places they’re allowed to go, the traits they’re allowed to have, and the way they interact with one another.

At the scale of atoms and nuclei, that structure is governed by a set of rules called quantum mechanics. Inherent to physics are “symmetries,” or behaviors that leave systems immune to changes. Particle symmetries can, perhaps profoundly, be explained by a field of mathematics called group theory, which studies certain collections of objects and the different actions that can be performed on those objects. The fact that quantum particles have a structure explainable by group theory offers us an elegant way of studying particles and more importantly, an elegant way of storing and manipulating data with quantum computers.

Group theory on its own is abstract, so we study it using a tool called representation theory. Representation theory turns groups into concrete “representations,” like a set of numbers organized into tables and the operations that can act on them. More specific to our purposes, in quantum mechanics, representation theory tells us how quantum objects transform—they transform according to a symmetry group. In fact, most of the numbers used to describe particles and atoms simply characterize specific representations.

All of this tells us that a natural guiding principle when approaching quantum algorithm development is to identify the symmetries hidden in problems. Group representation theory gives us the tools to leverage those symmetries to solve the problems at hand. More fundamentally, because symmetry groups act on the space of solutions of a physical system, understanding group symmetries tells us a lot about the properties of the possible solutions. Let's break down what that means.

The mathematical basis for the symmetric group

An example of such a symmetry group is “the symmetric group,” which describes the shuffling of a deck of distinguishable cards. Pick an initial order of the cards—for example, at position , at position , and at position :

-

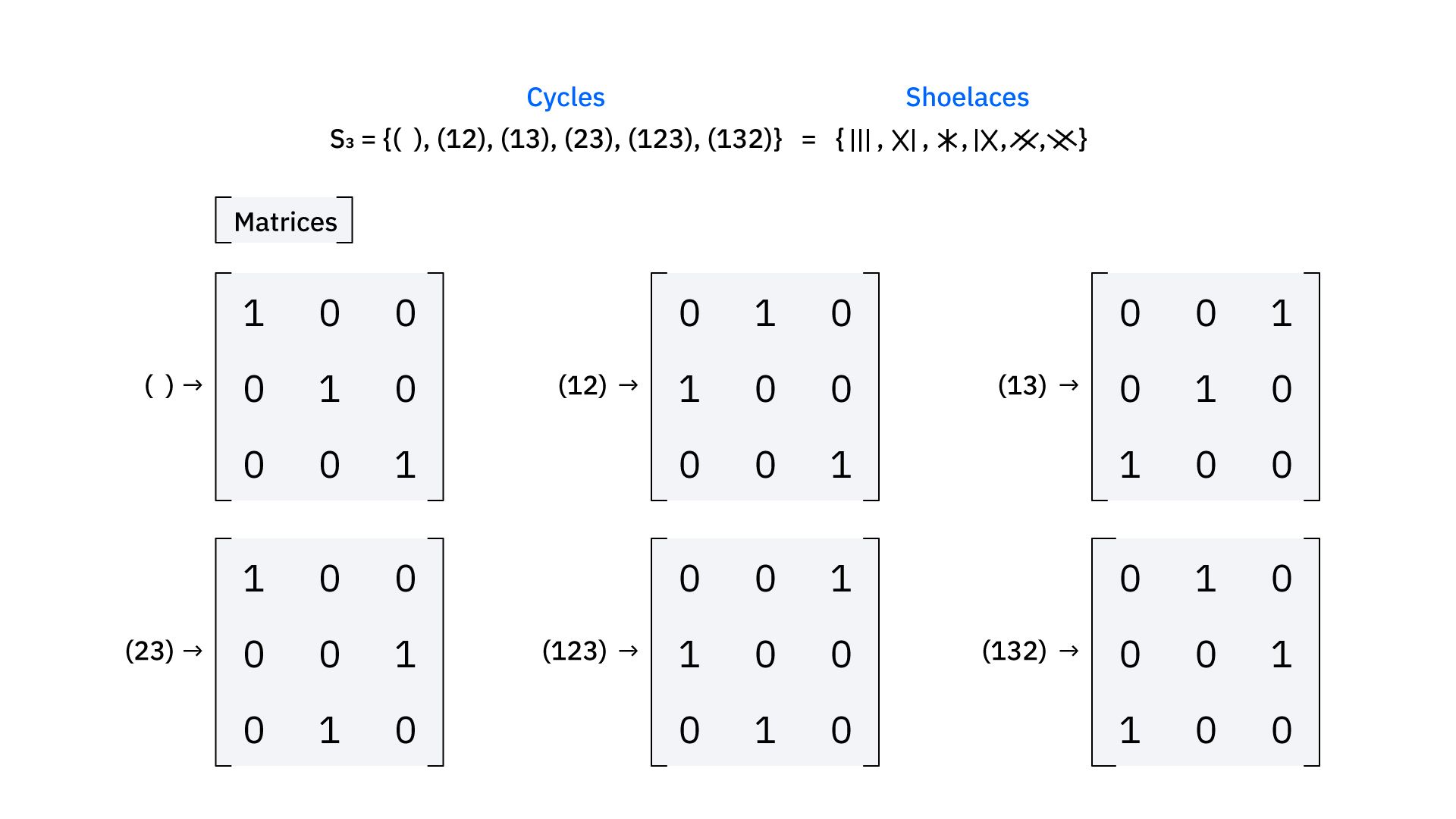

Reordering operations like “do nothing” or “swap cards at position and ” are called group elements.

-

Instead of writing “swap cards ” or “swap , , and ”, we save space by writing or . This way, applying to gives , while .

-

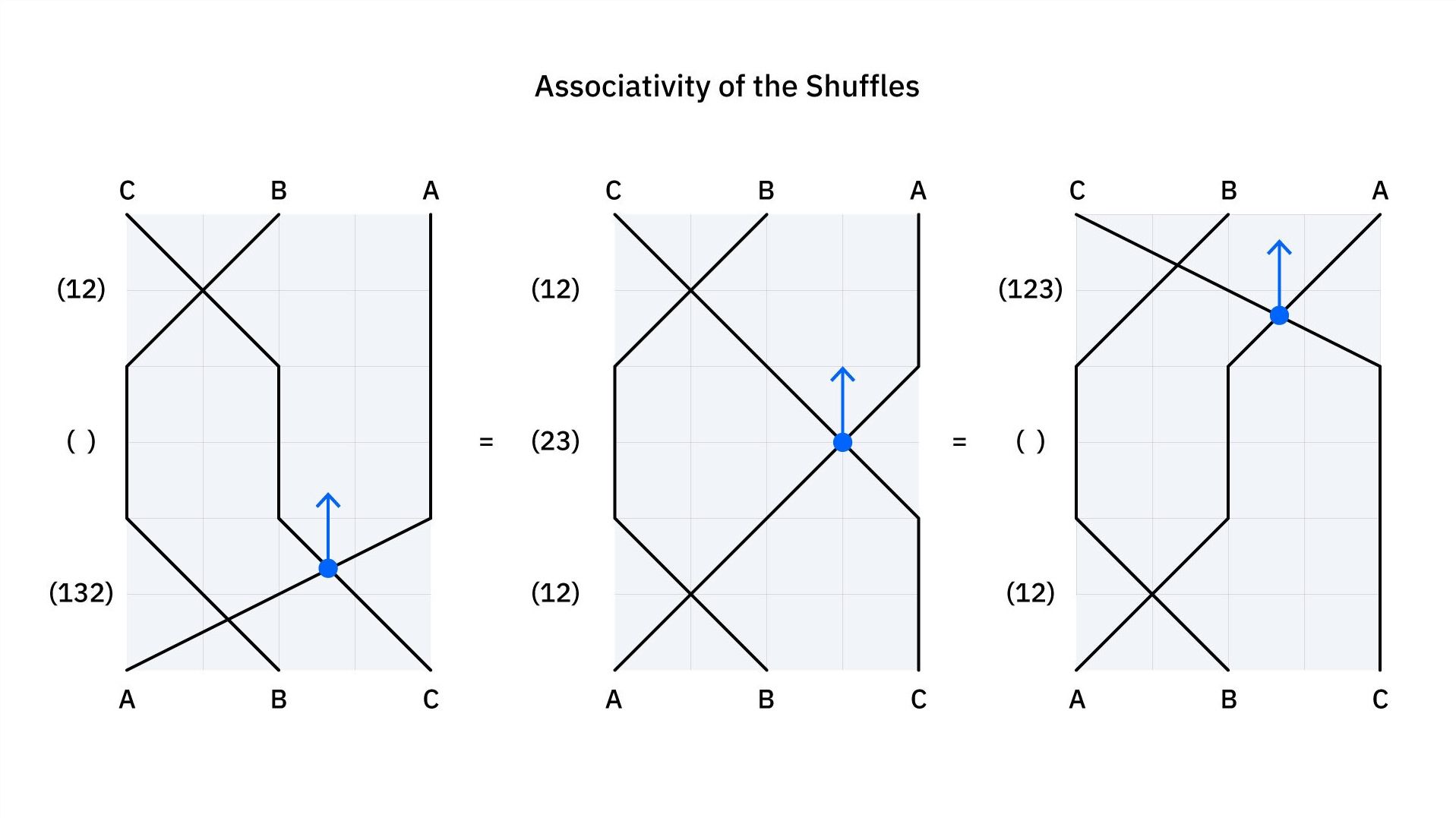

Any two group elements can be composed into a third; for example: is the same as . Order matters: , but .

-

There is always a “do nothing” swap and each shuffle can of course be undone; for example .

-

Lastly, shuffles are associative; , which really just makes sense of “bundling” the shuffles into the respective time steps.

This is all illustrated in the diagram below. The left is , the center is , and the right is .

Mathematicians want the freedom of representing the shuffles in all kinds of ways. That’s why they invented representation theory, a way of using matrices instead of cards to represent group actions. A matrix is a 2D array of numbers, which can be combined with other matrices using matrix multiplication. Representation matrices have the same number of rows and columns and for any group elements , , and , the matrix versions , , and must satisfy .

You can make many different representations of a group as long as you satisfy this condition. You can even make composite representations.

Let’s say you have three different representations of a group—, , and , each with their own set of matrices. Since they represent the same group, they have the same number of matrices. You can make a fourth representation, let’s just call it , by making a new matrix for each group member where is in the top left, every entry to the right and directly beneath ’s cells are . sits diagonally down and to the right, then more zeroes to the left, right, top, and bottom of ’s cells, and finally sits diagonally down from .

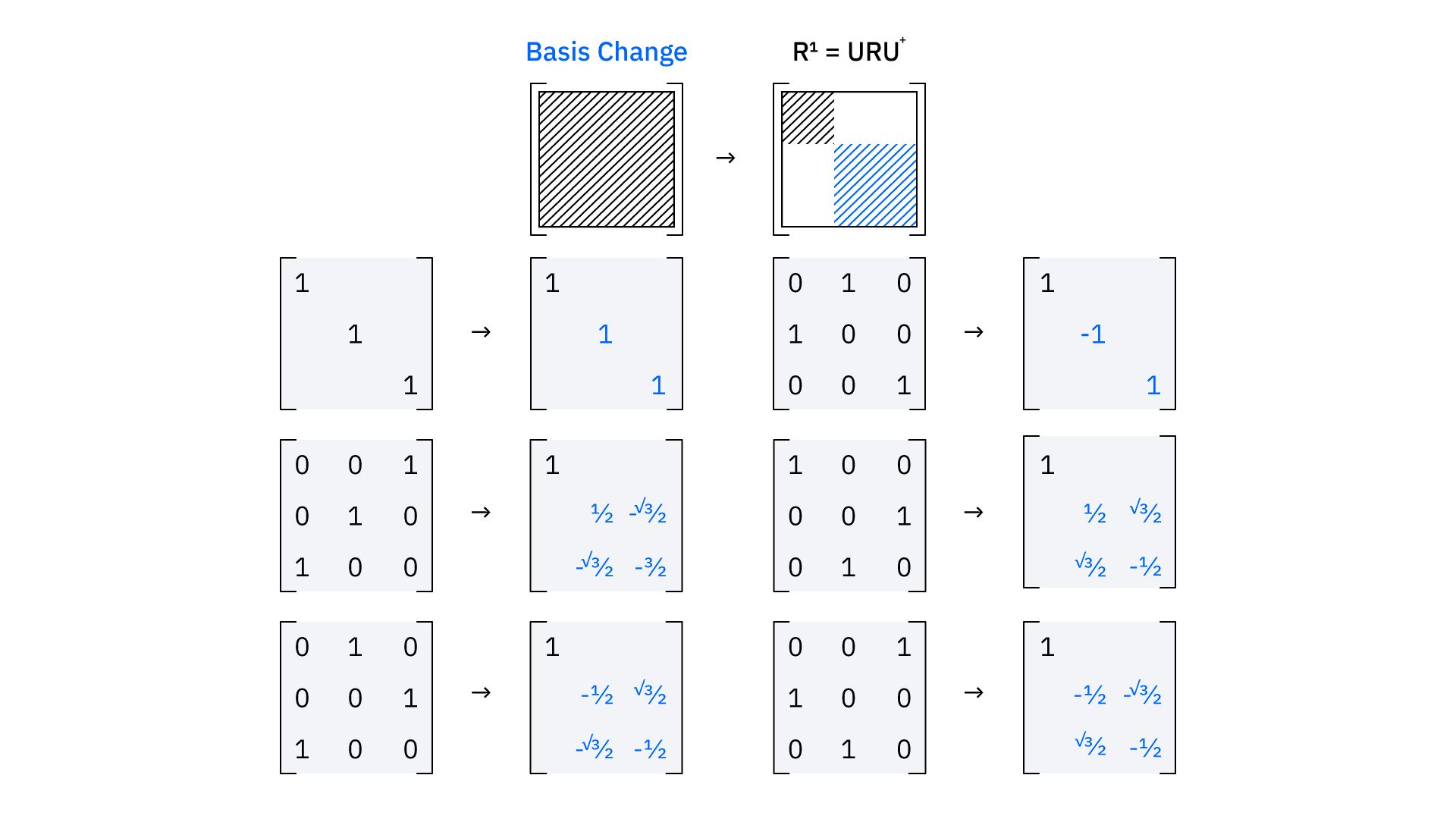

Any representation that can be transformed to this block-diagonal form using a “basis change” is called a reducible representation. Any representation which can’t be simplified in this way is called an irreducible representation.

Irreducible representations can appear multiple times inside reducible representations. The number of times a given irreducible appears is its multiplicity. If we made a reducible representation out of irreducible representations , , and , then would have a multiplicity of and would have a multiplicity of , while the 3-dimensional representation in the diagram has two irreducible representations, each appearing with unit multiplicity.

You can ask many questions about symmetric group representations. Among the most notable are the Kronecker coefficients: take two irreducible representations of the symmetric group and calculate their tensor product, which is yet another way of combining representations. This gives a new representation that again decomposes into irreducible representations, and the multiplicities of those irreducible representations are the Kronecker coefficients.

Computing Kronecker coefficients is very, very, very difficult on a classical computer, and hard classical problems are ripe areas for seeking quantum speedups.

How difficult is it?

On the surface, this problem has nothing in common with quantum—aside from the fact that it’s difficult to understand. However, quantum systems also evolve in a way that can be described by square unitary matrices, and quantum mechanics can be understood through representation theory. In fact, many key developments in quantum theory from influential physicists like Herman Weyl, Werner Heisenberg, and Eugene Wigner built heavily on representation theory.

Back in 2022, theoretical physicists Anirban Chowdhury, David Gosset, Pawel Wocjan, and principal investigator Sergey Bravyi were exploring one of the most fundamental questions in quantum. They asked how hard is it to estimate the basic properties of particles in thermal equilibrium, where heat neither enters nor leaves the system and, on average, no heat is transferred between the particles. Basically, a system that’s settled down.

They began by exploring the simplest “2-local” case—the case where the system can be represented by a sequence of individual actions occurring on neighboring particle pairs. Their proofs demonstrate that calculating the available free energy of this system—essentially the energy left over to do things with—is QMA-hard.

Being in the QMA problem class means that if someone gave you an estimate of the free energy along with a quantum “certificate”—in other words, a quantum state that serves as evidence for the problem’s solution—you could use the certificate and a quantum computer to efficiently verify whether the answer was correct. Being QMA-hard means it’s the hardest such problem and it is unlikely that there is an efficient quantum algorithm that finds the answer in the first place.

Importantly, they discovered that a general version of the problem asks to approximate how many linearly independent states can serve as the quantum certificate. They devised a new name for these kinds of problems—QXC, or “quantum approximate counting” problems. A problem is in QXC if its answer is an approximate number of solutions to a QMA problem.

Now, with QXC described, those theorists had a gut feeling that these QXC problems were hard, but not nearly as hard as the hardest problems for which a classical computer could count—but not necessarily calculate—the number of potential answers. They just needed to find such a problem. Given its profound synergies with mathematical descriptions of quantum particles, representation theory was a natural place to look.

In a 2024 paper, Bravyi’s team, now including Havlíček alongside fellow IBMers Anirban Chowdhury and Guanyu Zhu, found that for some cases, the problem of counting the Kronecker coefficients and other multiplicities of the symmetric group was in the QXC complexity class. Armed with the knowledge that quantum computers could efficiently make some inroads into this problem—if not by calculating the multiplicities, then at least by approximating how many there were—Havlíček and his collaborator, Martin Larocca of Los Alamos National Laboratory, went about devising a quantum algorithm to compute them. (Havlíček would also continue his work in this area as a member of Bravyi's team, which published a follow-up paper in PRX Quantum earlier this year.)

Digging up an old tool

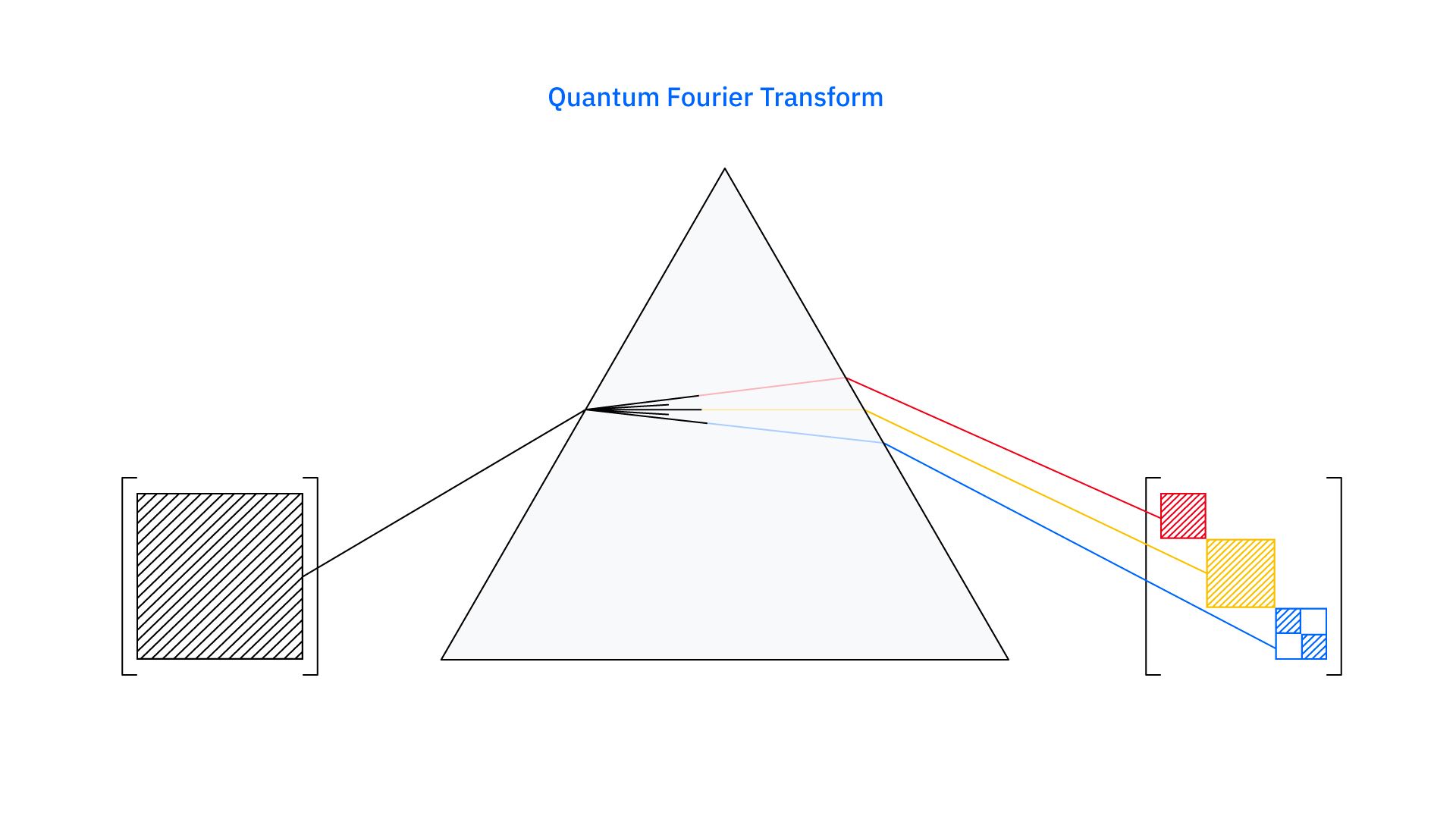

Havlíček and Larocca now had a hunch that they had identified a problem that could be computed more efficiently with a quantum computer than with a classical computer. Now, they needed to design an algorithm to crack it: and they turned to the quantum Fourier transform (QFT).

Fourier transform is a way of decomposing a signal into fundamental frequencies, each with an attached weight. The way nature breaks white light into the colors of a rainbow is pretty much the same thing.

In a similar way, the quantum Fourier transform (QFT) decomposes quantum states into simpler states with well-defined symmetries. It is the mathematical routine that underlies Shor’s algorithm, allowing us to factor numbers exponentially faster than a classical computer. A promising tool for modeling the energies of molecules called phase estimation also relies on QFT.

But here’s the rub. Physicists are very familiar with the phase estimation algorithm on “abelian” mathematical structures like addition or multiplication, where the order of mathematical operations doesn’t matter. But as we saw with the cards, the same is not true of the symmetric group. There is a natural generalization of QFT to non-abelian groups: a transform that decomposes states into components supported on individual irreducible representations. It even has an efficient quantum algorithm for the symmetric group.

However, applications of phase estimation for non-abelian groups—also called generalized phase estimation—have often led to disappointment.

“While this is a very natural extension of what has proven successful in the Abeilan case, it has not shown the same success” said Kristan Temme, head of the IBM Theory of Quantum Algorithms group. “People had really high hopes and aspirations for this procedure, but it historically hasn’t lived up to those”.

And yet, after hitting his head against the problem, Havlíček found that staring him in the face was an algorithm using phase estimation for the non-abelian symmetric group—an algorithm capable of computing these multiplicities on a quantum computer, even the Kronecker coefficients. Moreover, the algorithm was efficient on some subsets of inputs.

After searching the literature, Havlíček could find no classical algorithm that was anywhere near as efficient as this quantum algorithm. He conjectured that his algorithm demonstrated a super-polynomial speedup over the best classical method. We’re not talking classical sedans versus quantum race cars, but classical cars versus quantum rocket ships.

What’s more, this gave the world a new way of studying another mathematical problem that has remained open for decades in another field—algebraic combinatorics. This is a field of math that, simply put, analyzes different kinds of algebraic structures and their behaviors when handling discrete and finite objects—for example, tetris-block-like tables filled with numbers called Young Tableaux.

Algebraic combinatorics exists because these shapes can simply describe the properties of the symmetric group and other important mathematical structures. Answering whether the Kronecker coefficients hold meaning in this field—whether they count some number of shapes sharing some specific properties—is an open and important question.

Improving quantum and classical together

Havlíček’s claim was intentionally bold to attract the eyes of the experts in classical computing. And it did—the paper quickly fell into the lap of accomplished mathematician Greta Panova, a professor of mathematics at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and a leading expert on the Kronecker coefficients.

Panova looked closely at the problem in an arXiv preprint, and essentially disproved the conjecture by Havlíček and Larocca of superpolynomial speedup with a nontrivial improvement upon the previous state-of-the-art algorithm. However, even after disproving the stated conjecture, a peculiar polynomial speedup remained: Where the classical solution took on the order of time to run the problem based on some tunable parameter , quantum took .

Set to , and quantum goes as while classical goes as . Set to and quantum goes asymptotically as while classical takes —and the disparity grows quickly as increases. In short: it was still quantum race cars versus classical sedans. But even if further work disproves this speedup, the work holds symbolic importance for the field.

“There are these big open problems, and we had some ideas for how the formulas should look,” said Panova. “And now we suddenly have Fourier transforms from quantum algorithms. It gives new structure and new methods for us to understand these quantities.” In practice, progress may be slow—quantum is an entirely new field for mathematicians working in Panova’s corner of abstract algebra. But in an ideal world, mathematicians can begin to explore quantum computing concepts to help answer long-outstanding questions.

Havlíček remains cautiously optimistic about his new algorithm and hopes that the speedup holds. For now, he considers this work a challenge to the community. “It really feels like, what else works for quantum algorithms, if not this?” said Havlíček. “Our algorithms are so general that disproving the existence of a quantum speedup here comes with implications for other quantum algorithms. It is one of the key takeaways for me and also a reason why I explicitly flagged the conjecture.”

Havlíček is very excited about the new bridge between quantum computing and theoretical mathematics, and about the fact that mathematicians are taking the result seriously. He’s been invited to a mathematics conference to speak alongside Panova about the result.

Further, the work demonstrates a core mission of IBM Research: to uncover new algorithmic tools that outperform the best classical methods. Though dealing firmly in the realm of theoretical mathematics, identifying an area where generalized phase estimation provides a significant speedup over the best classical methods signposts toward more applied use cases that might yield significant value from quantum computing. They might even open entirely new applications or areas of study, in the way that hashing and the fast Fourier transform did with classical computers.

“This work was about taking a step back,” said Havlíček. “We’re looking deeper into the fundamentals defining not only how to get massive gains in computational performance, but enable things we couldn’t do before in terms of computational capabilities.”