The IBM Selectric was the most successful electric typewriter in history. With its distinctive type element — a spinning, bobbing mechanism often likened to a golf ball — it improved the productivity of typists and the appearance of their work. It offered multiple fonts and multiple alphabets while paving the way for IBM to enter the business of word processors and personal computers decades later. In 1978, IBM held 94% of the market for electric typewriters thanks to the Selectric, which for more than 25 years was the typewriter found on most office desks.

For good reason. Despite almost 90 years of modifications and improvements, the average typewriter circa 1960 still employed the same imperfect architecture introduced in 1873. A cylindrical platen, or carriage, moved back and forth, while a nest of type bars, one for each character, was activated by corresponding keys. It was a relatively effective system for getting words on paper, but the type bars would jam when keys were struck in quick succession, and the carriage would often force the paper out of alignment, causing whole rows to fall askew.

IBM invested decades of research to overcome these problems, culminating in the introduction of the Selectric in 1961. It replaced individual type bars with 88 characters positioned around the spherical type element, eliminating the jamming issue and the need for a carriage.

IBM entered the electronic typewriter business in 1933 with the purchase of the production facilities of Electromatic Typewriters. In 1946, the company unveiled the first of a number of innovations that would ultimately become defining features of the Selectric. In that year, Horace “Bud” Beattie, one of the principal designers of the IBM 407 Accounting Machine, received a patent for a “mushroom printer,” or an umbrella-shaped type element, intended for use on an accounting machine. He and IBM engineer John Hickerson, an aficionado of antique typewriters, built a working model and showed it to CEO Thomas J. Watson Sr. As Beattie later recalled, Watson broke into laughter and then said, “Bud, you must have been drunk when you designed that thing.”

Under Beattie’s direction, Hickerson worked on the typewriter along with a group of engineers led by Ronald Dodge, one of the first IBM Fellows, and Leon Palmer, who eventually held the lion’s share of the patents associated with the Selectric and would likewise be designated an IBM Fellow. By 1954 the team had completed a prototype, but it took seven more years to get the typewriter to market. The Selectric eventually consisted of some 2,800 parts.

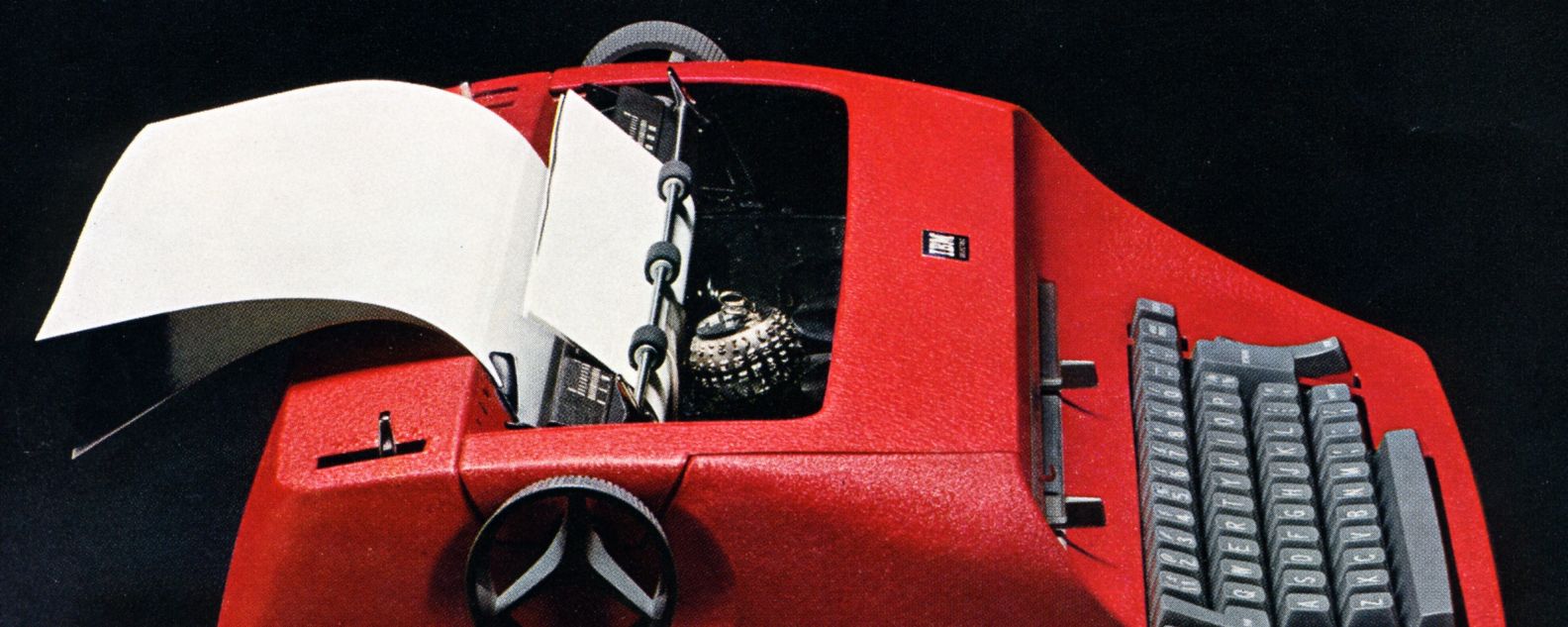

The mushroom was replaced by a spherical element measuring 1⅜ inch in diameter. When a typist pressed a key, the sphere would instantly tilt, rotate and progress across the page to ensure that the proper character would be imprinted in the appropriate spot, eliminating the need for a moving carriage. To minimize the rotation of the type element, lowercase letters were arranged on the front and uppercase letters on the back.

The type element was made of molded plastic and blasted with walnut shells — sand would have been too abrasive — to remove burrs. The last step was chrome-plating, for durability. The type element didn’t strike with as much force as type bars, so IBM’s type designers lengthened some serifs and shortened others to make the impressions more equal.

The aesthetics of the Selectric fell to Eliot Noyes, who served as consulting design director to IBM for 21 years. He drew inspiration for the industrial design from Italy’s Olivetti typewriters. The result became available in eight color combinations and is considered an icon of IBM’s history of industrial design and product innovation.

When it debuted on July 31, 1961, the Selectric could print 186 words a minute; its rotating cam shaft, devised by Palmer, allowed print characters to strike as quickly as 20 milliseconds apart. Six typefaces were available by substituting the type elements. Model 721, the smaller of the two Selectrics, could accept paper 11 inches wide. It cost USD 395 and weighed 31 pounds. The larger Model 725 could handle paper 15 inches wide, cost USD 445, and weighed in at 37 pounds. The Selectric keyboard was flatter than those employed by previous typewriters; the keys were ergonomically designed and contained a buckling spring mechanism that created just the right amount of resistance.

IBM sold 80,000 Selectrics in its first year — four times the company’s projections — and more than 13 million units in total. “You couldn’t get around to places fast enough to show people the equipment,” recalled Lou Fowler, an account manager in Columbia, South Carolina. “We would open our cases in the lobby of a large building. Within minutes, word would get around that the ‘bouncing ball typewriter’ or the ‘flying walnut machine’ was down the hall. People would stream in and place orders right on the spot.”

The Selectric continued to spur innovation long after its release. At USD 15 each, interchangeable type elements were soon available in languages including Hebrew, Athabascan and Braille. IBM introduced specialized type elements for formulas and statistics and an increasing range of fonts. With the addition in 1964 of a magnetic tape system for storing characters, the Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST) model became the first, albeit analog, word processor device. In 1973, the correcting Selectric used a new ink formula that didn’t penetrate the surface of paper, enabling typists to correct errors by lifting them off the page with a special sticky tape.

While it was eventually superseded by purpose-built personal computers and word processing software, the Selectric line showed the promise of combining electronic memory with a standard keyboard. By 1978, IBM’s Model 75 Electronic Typewriter could store 15,500 characters, or up to about 10 pages of double-spaced copy. The Selectric was also commandeered into service as one of the first computer terminals, functioning as the keyboard input on the IBM System/360. A modified version of the Selectric, dubbed the IBM 2741 Terminal, was adapted to plug into the System/360 and enabled a wider range of engineers and researchers to begin talking to and interacting with their computers.

The final Selectric, the Selectric III, was sold in the 1980s with more advanced word processing capabilities and a 96-character printing element. As personal computers and printers became more popular, the Selectric was officially retired in 1986. But there are still many fans of the iconic brand, and a quick search of the internet will reveal many well-used and lovingly restored machines selling at or even above the initial list price — more than three decades later.

By focusing on people, IBM has designed products, spaces and solutions that harmonize industry and art

The sleek and powerful black laptop computer became a staple of business productivity and a must-have status symbol

A USD 1,500 open-architecture machine became an industry standard and brought computing to the masses