7 July, 2021

Episode 06 — It’s about time for a history in Black design — part I

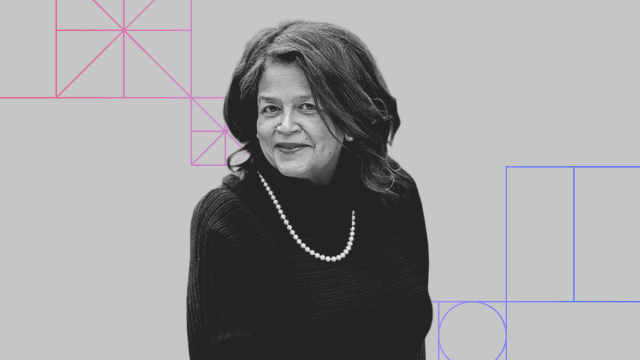

Listen in to part 1 of an exclusive interview with Dr. Cheryl D. Holmes Miller, as she details her learning experiences on her journey to a highly lauded design career. Dr. Miller shares how growing up in an activist household in the nation’s capitol, during a time that paralleled critical historical moments in Black history, sparked a legacy that continues to reverberate throughout the entire Black community.

Episode 07 — It’s about time for a history in Black design — part II

Join us for a continuation of Dr. Cheryl D. Holmes Miller’s renowned design career journey. In this episode, Dr. Miller takes us through her experiences in graduate school and out into the field during her early days as a young writer and designer. Listen in as she talks about fusing writing and design, how the impact of history and the cultural landscape influenced her work and molded her into the legend she is today.

Young Cheryl

1962

Capturing Black design history

“There’s no way possible that I’m going to be able to write as many books as that are needed to capture our history. My greatest work will be to lead the footnotes and the outlines [and] to tell you where things are. If you don’t know what’s in the card catalog, you don’t know what the research is, and that’s what’s important about trying to capture the ancestors of the elders. Who like I always say, you know, I’m old enough to have lived it, and young enough to remember it.”

Cheryl's press bio photo

1987

Additional resources

- Black Designers: Missing in Action (PRINT) by Dr. Cheryl D. Miller

- Black Designers: Still Missing in Action? (PRINT) by Dr. Cheryl D. Miller

- Black Designers: Forward in Action Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV (PRINT) by Dr. Cheryl D. Holmes-Miller

- More about Dr. Cheryl D. Miller cdholmesmiller.com

- Dr. Millers opening keynote for Where are the Black Designers 2021 Conference

- IBM’s announcement of Dr. Miller’s inaugural appointment as the 2021 Honorary IBM Design Scholar

- Dr. Miller announced as the 2021 Cooper Hewitt National Design Award Recipient

- Dr. Miller announced as the 2021 AIGA Medalist

Transcripts are edited for readability and clarity.

Nigel: Today I want to start off by sharing with you a few thoughts and words of wisdom from, from our ancestors. And this first thought comes from Madam C. J. Walker. One of the United States first ever female Black entrepreneurs and she is the first female self-made millionaire as an entrepreneur.

She said, “don’t sit down and wait for the opportunities to come. Get up and make them.” Secondly, this one comes from Ruby Bridges. She says, “Don’t follow the path, go where there is no path and begin the trail.” That’s Ruby Bridges, an American civil rights activist.

She was the first Black child to desegregate the all-White Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana in 1960. And at IBM, especially in our work in racial equity and design, we have a concept of the second pillar; are those of us in the lived experience of being Black in America and in design are the first pillar in our work. And second pillar, are our allies, and we like this idea of equally yoked pillars that support the work from society’s second pillar, if you will.

This third quote comes from Bill Gates. Don’t let complexity stop you. Be activists. Take on the big inequities, it will be one of the great experiences of your lives. And with those three ideas, I want to bring in my guest for today. She is a preeminent designer in our industry. Someone who’s been respected for multiple decades, someone who I’ve had the pleasure to get to know as she inspires me in ways that no one else has to be honest.

She’s inspired thousands in her career. She’s number one, a designer an educator, an entrepreneur and speaker. Welcome Ms. Cheryl D. Miller to the podcast.

Cheryl: Thank you so much for having me.

Nigel: And so that we get to know you a little bit better and—and set the context. I always like to start off with a little bit about where folks come from. Would you mind sharing with us a little bit about where you grew up and where you ended up going to school?

Cheryl: I am from Washington D.C. and I’m a D.C. girl and I’m very proud. My parents were Howard University graduates. And right before my father passed away, he passed away young, he was actually one of their alumni gala awardees 1969, I believe. And I grew up on Howard’s Campus with them. They were very active alum and my mom worked on campus and in health services she was registered nurse for the college. So I grew up with homecoming and footballs and football games. And I grew up —all of my friends took music at the college of fine arts or dance. And I always found my way to the gallery. They have a museum there, so I grew up sitting in the gallery, waiting on my parents and being a part of a kid just running through Howard fine arts. And so, that’s a part of my early exposure in DC. And of course, Washington is a museums town.

I grew up with all the, you know, on a good day, they throw the kids on the bus and the field trip was going to the mall, going to the museums. I grew up naturally at the Portrait Gallery and the Gallery of Art. And then on the other side of town where the Corcoran School — the Corcoran Museum, Hirshhorn museum, so Washington, it’s a museum town and all of that exposure was around me.

My parents had friends from Howard. They were, you know, a couple, gregarious. And my godmother was a painter, and my father had a best friend who was a type of a life and look photographer, events photographer, and there were two major photographers that were capturing the Negro socialite, if you will, Addison Scurlock. And what Addison Scurlock didn’t do, my dad’s friend Ed Hubbard did. And so I grew up with Ed’s dark room in his house. We would go visit. All the Howard grads and alumni still continued to gather and enjoy entertainment together. And, you know, I was just a kid that my dad’s knee was all of that.

You’ll hear me say often I grew up during the technology transitional period of listening to either radio stations for shows that also were kind of bridging to this new media television. I might listen to a radio show in an afternoon and then cut the black and white TV on and see, I Love Lucy.

I grew up, you could still hear radio shows. The new concept of black and white TV, I could see a show. And then as the years kind of moved and Papa got a color TV and 1962, I think the color TV came up and came out and I could — six o’clock the peacock—peacock came on. So it turned for black and white to color.

We only had only had color TV after six o’clock with the news. And you know, this is an era of brand-new Mickey Mouse Club and animation. And we used to have a guy on TV, Jon Gnagy. He’s kinda like the back in the day, Bob Ross. And he would come on with charcoal drawing lessons and all of these things inspired me. Ed, my godmother.

My father had an alpha friend, I believe. It was a high school art teacher, McKinley High. I have a lot of things to kind of like spark the interest. And so I, I would, I claim my early memories that are they’re very crystal clear. I started my journey in art when I was three years old and started winning awards at the age of 10.

And I think at that point is when I began to take it seriously for myself. I had a serious interest, but I claimed the path when I was 10. I won an award and ended up on the cover of the Washington Post and the Washington Star and right at that juncture, I realized that I was called to something greater than just a kid’s interest.

Nigel: And this is an interesting time in our nation’s history, right? So I’m curious about race relations at that time. And I know you have a really interesting relationship with identity and race, and I was hoping you could share a little bit about what that meant to you in that timeframe of fifties, sixties, seventies, even as you were coming up. I love the influences of the university and the photographers and television, and the technology. Was race an issue that that was talked about much in the home?

Cheryl: We had to reconcile that we, our family, was an anomaly. And it’s only really been in my adult life that, and after, I would say, after my mother passed away, did I really reconcile myself to the fact that I am multi-racial and multi-ethnic and I was raised African American and I think that my father, in particular, he had great aspirations.

He was, he had a big goal to become the mayor of Washington D.C. And he was eminent to that pathway and after Walter Washington. So my father’s tenure in Washington and his interest to become mayor is sandwiched between Mary and Barry and Walter Washington. My father passed away right in the middle of this. Mary and Barry pretty much picked up where Papa left off.

So Papa is this unsung hero in the middle of federal and Washington D.C., local government history. And he was extremely active with the federal government, and he was working the White House because before then there was not—before home rule, you had to be appointed as commissioner mayor. And my father was on a track to get appointed from the — really, he was on track to get appointed from the Nixon Administration.

He had been working the Johnson Administration. With relationships and working with Walter Washington and his hope was to be appointed commissioner mayor after Washington and part of his political aspirations for D.C., we all had to reconcile ourselves that we were visually an anomaly. Okay. My, my mother was uniquely Filipino Creole American with this incredible Danish West Indies heritage.

She’s Filipino structured physically. Physiology with an island accent, very much of an anomaly. A very beautiful woman and which in Washington, D.C., she was —my mother was just beautiful. That’s the only thing I can tell you. And it drew a lot of attention just going out on, going to the mall, going to the, you know, we were an interesting looking family without explanation. All right.

And my father himself was mixed race. Out of four — you’ll always hear me saying I had four grandparents. Four different races, four different places. And because of his political aspiration and this plan, it was best for us to be one drop in the African American lifestyle culture. We tucked down into my paternal grandmother’s life.

So if I have four grandparents. Four different places. four different races. I have my mother; my paternal grandmother is African American. And so it was just easy in Washington, not to bring attention and bring to light or to celebrate all of this ethnicity, and racial ambiguity and anomaly. My father was trying to become mayor Washington.

So listen, we were Black folks, but on the inside of the house, we were, you know, I, I have a Western Indian mother, specifically a Danish West Indian mother, which is my family is, is Indigenous. They were there, they were there before Carnival Cruise and they were there before the Americans. My grandmother was a Danish woman and Danish mix and mix from the demand of slave trade.

And you know, all my heritage and my lectures, I, I would say on my own family historian and expert, when it comes to the Danish Ghanaian slave trade. My family, my maternal family is a derivative work of this. And one of the things that I’ve reconciled myself to is that World War I brought my grandfather, who was Filipino, from Cavite Philippines. It’s mariner’s town outside of Manila Bay, brought my grandfather in with the us Navy.

What in the islands, we call Transfer Day, which is March 31st, 1917. And coming, I just recently gave a lecture at the Caribbean Library and my research always brings me answers to a brokenness of being what we call now — you know, I call myself the OG BIPOC. I’ll always be a Black woman. I’ll always be African American, but I’ve accepted that I’m all these other things as well.

And I am Filipino as well. And that, that history comes with a brokenness of what I had no idea until I really researched a lecture that I just recently did. I knew the situation in World War I was really bad for African Americans. African American men in the service. And Nigel, I found a very gripping documentary.

I didn’t expect to find it, and I’m a researcher. And somehow, I don’t — I find things that become important to my scholarship. And I found a documentary where they will — historians were talking about World War I and the oppression that African American sailors were experiencing at the hand of President Woodrow Wilson and Josephus Daniels who was the Secretary of Navy. But there was this strategic effort to hinder the progress of them, Black men, after Emancipation, and Woodrow Wilson implemented 1913; he segregated the armed services.

Well, all of my research and my writing, I knew that, but what I didn’t know, and I heard in the documentary was this strategic plan implemented by Josephus Daniels, who ran the Navy and the documentary pointed to the fact that they took the African American sailors out of the Navy. And because of the Spanish American War, they were also colonizing the Philippines. Their strategy was to use Filipinos to replace the Negroes as MATT 2, which is your mess labor. And it was something in the documentary where the documentary was not about Filipino sailors. It was about the systemic racist practice against the Black man in the Navy. It was a strategic plan to get rid of his presence in the Navy World War I. I listened to the documentary several times, Nigel, and I realized that my grandfather had been sent as solution to the plan to remove an anomaly, the Black man out of the U.S. Navy World War I.

So the United States wanted to purchase the islands from Denmark. Everyone did not want Germany to get those islands. It was a calling station, had suffered loss from the sugar industry, a hurricane left the Island in a place where Denmark didn’t want to have anything to do with it. My mother — my grandmother was 17 years old at this time, so she’s Indigenous.

And so the Americans came, they bought the islands for $25 million, and the Americans came March 31st, 1917. They lowered the Danish flag and up went the U.S. flag and that’s called Transfer Day. And my grandfather was mess labor on the Navy executive yachts that came in to establish democracy. Given the turbulent time a bit, the islands, my grandmother and her girlfriend, they were —they were mixed race derivative of the slave trade and the Danes and colonizers. And the fair skin women were used on main street, which is like most islands you know, the Gucci runway where you get your duty-free, perfumes, jewelry and things, and they would use the mixed-race girls to make the European travelers comfortable. And the African diaspora women, they were your coal women working the steamboats. And my grandmother was 17, and her girlfriends who were sales girls for duty-free convenience and ease for the — paradises always been paradise before Carnival Cruise. And so it was definitely the wealthy coming in Scandinavian cruisers, ship liners.

You know they met the Americans and the U.S. Navy that came in, they met them at the USL. And my grandfather was a part of the Filipino American Navy that came and seven, eight, seven or eight, or Filipinos came with the Americans, which established the first Filipino community, the U.S. American community on the island of St. Thomas. And so I come from this, you know, she married my grandfather. He gave her three Filipino babies and he disappeared from my mother’s life. Very interesting. My mother fit our physiology. She’s totally, she was totally Filipino in appearance, and she wanted to come to America to go to school.

And from her, from her point of departure, she found her way to the Freedmen’s Hospital Nursing Corps and came to Howard’s campus to go to college. And she was part of Freedman’s Hospital Nursing Corps in 1942. And my father was on campus, and he was gregarious. Studied social worker — study social working and I’m Washingtonian with four, I think fourth generation Washingtonians.

And our story is my father’s unique ethnicity and race himself. Like I said, I have one grandparent. His mom was African American, but his father was White and Native American. We didn’t know whether my grandfather was White. We didn’t, we didn’t know. And it was always a mystery. No one ever talked about these complexities because Papa was working in the White House.

It’s like, I’m going to be mayor. We can’t — we’re going to play mom off, like Lena Horne. And we’re just, we’re just, we know this is a little different, but we just got to be fair skin light folks. I got to work the White House. I want to be mayor. all of that complexity, we just didn’t, we just didn’t deal with it. We didn’t deal with it.

And I’ve had to deal with it. I personally have had to deal with it, and it’s been dealt with, it’s been, it’s been dealt with.

Nigel: You ended up attending university at Rhode Island School of Design, RISD. And you know, RISD part of the sort of connected Ivy League family of educational institutions, of course, in the Northeast. I’m curious a little bit about that experience, you know, at that time. And, and how did race — and I think your stories are telling are from recent meaning adult revelations about your family, and you’re mixing in obviously what you knew about your family as you were growing up. But as you’re 18, 17, 19, and that age sort of range, what was it like being what you were while entering and stepping foot on, on this predominantly White campus? Even farther North? Yeah.

Cheryl: Well, first off, I’ve never seen — my father made sure it was, I would say it was pretty much my father’s decision to make sure that we pick the culture. So out of this complexity of ethnicity and race and multiculturalism, I mean, he said, look, we’re going to be African American in that, you know, colloquial to the era and we’re Negros.

And so I was raised, I was raised thinking nothing else. Okay. So I think out of my lens, I’m a Black woman, but what I did not realize is once I left Washington, I did not realize that I was not necessarily perceived as Black. So once you start moving further out, okay, and the less you’re aware—aware of down South, and this is the way — this is the way, you know, folks are made.

You know, I was more of an anomaly, but I got grouped into a minority recruitment program. See, I was a rising senior when Martin Luther King was assassinated and specifically at that juncture, that’s why I’m, — I’ve been where we are, except for the pandemic. I mean, back then I was ducking and dodging polio. Here, I’m ducking and dodging COVID, you know we’re on a 50-year cycle.

I’ll have been here before and I started college touring and visiting schools. And my father asking me about college really starting right with Martin Luther King being assassinated and Washington burning. And a part of the reparation, the Ivy league schools started. It would — they came into the urban cities and I, based on just coming in and principal handing recruiters, folders student folders, everybody, every, every kid in Washington got an invitation to apply someplace.

And I always chuckle Nigel. I was — I was invited to apply to Wellesley. I discovered Rhode Island because my father, you know, by the time I was in high school, I was winning awards, you know, all the way from where the first part of our discussion. I knew I wanted to go to art school. And so my dad said to me, one afternoon, we have this library and he call me in, and he says, you have a plan for college?

I said, no, I don’t have a plan for college. It’s this, we’ll go get a plan and come back. And I did a little research and I had discovered art college. And this is a time in the history of academia and school you could become — so I’ve always lived and straddled in this transitional spot. Like I said, I could listen to radio, and I could watch TV. To be, to be an artist or commercial artists, you could go two routes. You could go to art institute and then get picked up as an apprentice. And then from the apprentice, you would work your way up from the pay stop table to the layout table, to the design table, to the art direction. It was all based on apprenticeship in art institute. You could go that path.

So all of the schools were like that. And then there became this cat and they said accreditation process. And right there, the schools were becoming, many of the art institutes were becoming accredited and offering BFA’s and I came home with a plan. I said, “Pop, there is art co — there’s this thing called art college.”

He, he didn’t want me to go the technical route, the apprenticeship route. He didn’t want me to go to art institute. So I said, well, any — and we said to me, make sure you have a backup plan for academics. So with a little research, I discovered art college, and I never forget, I came home I said, “I’m going to go to art college.”

I can, and there are few of them. And this, this new concept. I remember, I was telling him I can get a BFA for you. I can get a bachelor’s for you and study art for me, and these schools opened up. They all were there together, opening up. What I did not know, and that’s what my research and a lot of my lectures now, is that March 1970, there were a couple of things going on that I had no idea about.

Rhode Island School of Design was addressing student demands in March of 1974 for diversity on its campus. This is, this is locate. I always want folks to locate me. I’m right. This is happening right after where the community is raw from the assassination of Martin Luther King. And the schools are in this reparation mode.

And I believe schools open up and they came down looking for kids to do something for the community. I just happened to drop onto the platform of Rhode Island’s recruitment program, because there were — they were in the middle of a student take down, 1970. There’s a demand letter. You know, that, you know, I use it as research.

I think it’s in one of my articles. I talk about the call of the students then to diversify and RISD develop the minority recruitment program. And with that said, I applied to — I applied to Rhode Island. And I always say I had an opportunity to go to Wellesley, English lit and to be a writer. I probably wouldn’t have been successful at it.

I find it curious. I went to RISD, I’m a writer, now I have everything to talk about. So yeah, a writer without something to talk about is not writing. And so at least the journey has given me something to write about, and so I ended up being recruited because I was going there anyway.

And then I found out that RISD had a formal program that was in response to student demand for diversity on campus. And 40 of us landed on RISD beach September 1970, and I got one experience is all I can say. And what I did not know, what I did not know was that in New York City there would have been — and this is in one of my lectures, the history of where the Black designers is my 50-year history. I talk about the trajectory of it. What I didn’t know, and I found a piece of, you know, I love my footnotes. The April/May 1970 issue. Page 78 of Communication Arts outlines gives a full explanation of a piece of fractal — fractal of Black graphic design and history that we will see on the internet.

And that is two fractals that float around, and they end up in the blogs and the students use it. But I wanna, I want to give you a rich footnote of where you can find a thorough, thorough explanation of this fractal. There’s a fractal. It says Rhode Island School of Design at the top. It’s a flyer.

And it says Blacks in, I think it’s Blacks and Blacks in Communication Arts or something like that. It’s Dorothy Hayes exhibit, and so that fractal is around. It’s a pollster and it lists 49 Black designers in New York City, and she starts this advocacy. She wants everyone to know that these designers in New York is 49 of them.

44-45 are men, four or five of them are women. And she’s barreling down this awareness. Print magazine writes about her. Blacks and the Black experience in 1968 or 69, they publish. But it’s this report Communication Arts April/May issue 1970 gives you full magazine article, feature /article explanation of this fractal that we are so hungry to find out what it’s about.

There’s another Twitter fractal that tells us this show. Herb Lubalin and George Alden helped to sponsor the show. The show first was at the Composing Room in New York, and it appears at the Gary Mansion at Rhode Island School of Design in April of 1970, somewhat in the response to, can we get some diversity on this campus?

So two things Rhode Island did: they allowed this exhibition to come in, Dorothy’s exhibition, and they started they started the minority recruitment program to try to bring diversity to the campus this is one of the things that is important with some of my work that I’m trying to do now is to leave oral traditions, footnotes.

I, there’s no way possible that I’m going to be able to write as many books as that are needed to capture our history as much as memorializing oral tradition and these types of facts. You know 40 colleagues have joined with me to open up the history of Black graphic design in North America at Stanford University.

You know, I, my, my professional collection is there Cheryl D. Miller collection at Stanford. And during this pandemic, I used it as sabbatical. There have been several things, projects that I developed, and that was one. Could I get my friends and colleagues to donate to a collection so that eventually there can be a database for future scholarship.

And with that said, all of these fractals, all I can do, like I said, if I, if you get one or two history books out of me it will be good. My greatest work will be to lead the footnotes and the outlines to tell you where things are. So as an example, this Communication Art book, you’re not going to find it online.

So when the scholars and the young scholars want to do their projects and things, all the blogs look like cause you — you Google the same, you Google the same information, and it all comes up. Okay, so a part of what I’m able to do is to remember. I remember, and all of these things weren’t online, these stories are in Communication Arts, a magazine, Print magazine.

If you don’t know what’s in the card catalog, you don’t know what the research and that’s what’s important about trying to capture the ancestors of the elders. Who like I always say, you know, I’m old enough to have lived it, and young enough to remember it. You want me to write it down. I might not be able to write the whole thing down, but you want me to write it down.

You want my friends to write it down because a lot of our stories are in card catalogs and we did not cross over the technology, technological divide and wherever Google started, wherever you want to track that, you know, 1997, eight, nine, and following forward 2000 we’re, we’re not, we’re not digitized.

Some of these stories are not digitized, and if you want to see the original New York designers, I’ll repeat it again. Because only thing you can find, if at all, you’re going to find this fractal of this pollster. You’re going to find this Twitter post and you’re going to see a story of — I think Letterform just did a story, The Black Experience, a reprint of Print magazine.

Okay, you’re going to see these pieces of the story. If you want to see the primary first recorded cadre of Black graphic designers who would be synoptic or parallel to the new school or the pushpin group. Okay, in fact, I’m doing a review treater for pollster house on pushpin, and this is one of my footnotes.

All right. That that I’m using is coming from Communication Arts. Page 78. Remember now, Miller was telling you this. Don’t steal — don’t take my research. Footnote lady and I always give my credits. So everybody, I heard this from Cheryl Miller, then you can trust it if you heard it from Cheryl Miller. It is so, okay?

Pride myself on that, but if you want the full report on the original 49African-American Black graphic designers, mostly men and four or five women, you’re going to find that on, I think it’s page 79 of the April/May 1970 issue of Communication Arts magazine and that is not online. You would have to know the book. There is an exhibit, it’s entitled An Exhibition by Black Artists and yeah, and it reads when, when designer Dorothy Hayes first came to New York in 1957, she found — she found few blacks in the art and design profession.

She vowed that if I made it, I would never turn my back on any black person who came to me for advice and information and who really wanted to learn. This exhibition is part of her total effort and keeping that promise. It is — this page 98, I’m sorry, page 98 and with that said you would have to have a copy of that magazine.

And so our history, it begins further back than that. But when we want to talk about who was there in New York with Push Pin, who was, who was there in the —when you always hear me say, did Milton Glaser really have to do Mahalia Jackson? Listen, listen, I have — my work has put so much in perspective. I’m 15 years younger than this cadre where we see this fractal. I’m 10, 15 years younger than those original New York art directors that are listed in this exhibition.

It wasn’t until my journey with decolonizing, the history of graphic design did I realize how racist New York City was during that era, but by the grace of God, any of us got work.

Transcripts are edited for readability and clarity.

Nigel: So, Pratt Institute there in New York, we’re jumping ahead a little bit.

Nigel: The thesis work you did; this is now into grad school. What, what motivated that thesis work? And how did that research come to play a part in your thinking from there on? As, as it relates to your role and your legacy? And, and were you aware at that point that there was this calling while you were doing this graduate work?

Cheryl: I’ve known that I was called, but I don’t— I didn’t know, specifically. When I say called — the fact that I started so young. I’ve been directed slash driven since I can remember. I’ve been insistent that I would be a visual artist. I’ve known nothing else. I have dreamed nothing else. I’ve done nothing else. It’s been a straight shot. Thus, there was something in me from the time I was a kid. I saved everything, you know, because I had to have a collection.

I says, well, it starts with— I saved everything. I’ve always known, Nigel. It’s like, how did Michael Jackson know that he would sing? How did Whitney Houston know that she would sing? How did Judy Garland know that she would sing? They started early. You know, I just — and life has allowed me not to burn out. I started young and I was clear, very young.

I had seen a disparity in practice and education in Washington, D.C. So, all of that, that we had talked about in my upbringing, I wanted to leave Washington. I wanted to see something else. And when I finished all of my primary art education, I went back to Washington, and I saw this disparity. Washington is a government town. It’s not a corporate town and it’s a fine arts town. So, all of the universities — Howard has a dynamic — it’s always had a dynamic fine arts department. You have American University, Georgetown University, Maryland University. All these universities with dynamic fine art programs spilling into a government town and after graduation there are no jobs for fine artists who want to be graphic designers.

They’re just like, well, you plant broccoli. You hope for broccoli. You don’t plant broccoli and say, oh my gosh, why didn’t tomatoes grow? And so, you’ve got an academic area that produces the finest of fine arts and painters and sculptors and mixed media. And now everybody’s around Washington in a government town looking for work. And I’m like, “how far are we going to go with that campus?” And government is not even, there’s not even a corporate population.

Okay, it’s association town and it’s a government town. And back then to get a government job as a graphic artist —okay, forget all these fancy names now they have for it. You — it was difficult. You had to forget the portfolio. The federal government, you had to pass the civil service exam. The same exam for a secretary or a GS20, everybody. For you to get in the government, you had to pass a civil service exam.

And once you pass that exam, then you went to your particular category. That was not an exam easy to pass, number one. It was made, so folks couldn’t get in. All right. So, I don’t even know if it still exists, but back then, if you wanted to work for the federal government, you had to pass civil service.

So, you could find — and where, where a lot of us are back then, we were in — there’s — I have beautiful history notes. We were — we’re the people who were —Blacks who made all the money. We were down in the treasury department and the pressure programs for printing. And I can’t call his name. I should be able to call his name for all of these notes that I keep. All I know is a gentleman and his team design — Black men designed a hundred-dollar bill.

I can’t call him his name. I should be able to. Oh yeah, listen. And Courtney, I love Courtney. She is part of Harvard— Harvard graduate conference. She said Ms. Miller, my, my grandfather designed the hundred-dollar bill. I said really? And I know the treasury department, so reading about him and his ment —mentees and we, we, we printed the money. You could get into these programs with the federal government. We printed the money; we designed the currency. All right. So, these are things that even like Georg — Georg Olden, when we see him on YouTube, you know, they — the government stamp, the emancipation stamp.

These were areas where we could work. So, I saw this problem and their associations. So, what your little art departments and associations, public affairs, and community offices — in all of these associations, cause it’s a lobbyist town. One, one or two corporations. I think Marriott was there, and M&M Mars was there.

No, no corporations. Okay. So, you got a pool of university kids and Black kids all have fine art degrees, not a great job market. And then, oh, by the way, you have local government. You have D.C. government and federal government. And the only way that you could get any of that work was as a subcontractor — and try to be a subcontractor with U.S. federal government.

Okay. Try to get that certification. These are not things that are easily attainable. And so, what I saw was in the Mid-Atlantic. I saw this big pool of people dropping into the abyss and especially the Black designer. Though, the Black painter, fine artists, mixed media artist who had degrees from local universities, not being able to address even the little opportunity in Washington, D.C., because it’s a government town.

And I saw in essence, a suffering community after the civil rights movement. Trained for one thing and got an “oh, aha experience” at the end of it. That what am I going to do with a fine arts degree in a town that doesn’t have a whole lot of graphic design work anyway. That if I could get, it would be difficult to get any way at best.

And I saw the suffering. And the only reason that it escaped me is that I left, and I was trained specifically as a designer. I came back and simply put; I was qualified to address a design job. So, by the time I got to New York and I, I, I prospered as a broadcast graphic designer, art director. I worked all —I was a broadcast designer and I’ve always had a knack for winning awards. I, I just— I just have a knack for it. I was a broadcast design award winner.

And I came into New York city with a television portfolio and a high awareness of this disparity, especially from a community that is predominantly Black. Having fine art degrees and not being able to get work as — back then, commercial artists or graphic artists, and I saw the suffering and I said, there’s a problem. So, I knew the problem when I —and I had missed the problem cause simply one and one is two. I planted broccoli and I got broccoli. I wanted to be my graphic designer. I started, I came back, I got a job, like one and one is two campers, okay.

But I saw people who didn’t, didn’t, didn’t take that linear step and fall into an abyss. And simple things and not being able to take care of your family. You know, can’t pay your rent, can’t pay your car note, walking around with a portfolio that’s full of painting and drawing and like everybody’s going well, “Yeah, that’s nice and what?” And so, in a community that’s predominantly urban and Black to see a lot of that. And then I would hold portfolio reviews and it would break my heart.

Years of portfolios that — what can I say, they don’t fit a commercial platform. You can’t address anything except what you went to study. You went to study, which is beautiful, but this job requires this. All right. So, I saw the suffering, Nigel. Decades, the days of it, months of it, you know, I practiced 10 years. I saw a decade of Mid-Atlantic you went to school for one thing and now you have to eat.

Nigel: And so, did you, when you started at Pratt, did you go in with — so you went in with that knowledge, perspective, and experience, but did you know you’re going to study this particular topic?

Cheryl: No. What happened is because of my portfolio, I was given approximately half of the degree based on my portfolio and professional experience. So, when I applied, they reviewed my portfolio and gave me half. They gave me half of the degree based on the portfolio and told me to take classes and pay the tuition and be along my way.

Well, I did that, and I focused on business and other things, all right. That I could study. And when I got to the end, it was time to do my thesis. Etan Manasse was the chair of graduate design, and he said to me specifically — I don’t know anybody else. I don’t know if this was across the platform, all the graduates, or whatever he just said to me— I’ll never forget it, and you can quote me. I say the same thing over and over. It’s all on YouTube, everybody’s interview. “Cheryl, you cannot design your thesis, no design project for you.” I want you, he said, “I want you to make a contribution to the industry.” And I looked at him and I said, “You don’t want me to do a design project?”

He said, “Cheryl, a design project would be too easy for you. You — I want you to make a contribution to the industry.” Well, I knew exactly what he meant. And I — which was a whole nother, — it would take a whole nother interview. My academic writing coach for 50 years —I never had a design mentor, but I had an academic writing mentor.

The acclaim —the acclaimed Dr. Leslie King Hammond was —has always been my academic coach. And I said —I called Dr. Hammond and I said — we call Dr. Leslie, and said, “Dr. Leslie, Pratt’s not letting me graduate with a design project, and I was given a charge to make a contribution to my industry.” And so, we both kind of said, “Well, we know what that means.”

I said yep, I’m going to have to write my way through this. So, I knew the problem, and what we did and how I was coached was pretty much by the time I got to study theology. By the time I got to seminary, my school doesn’t necessarily pride itself on raising ministers. It prides itself on raising scholars and historians; critical thinking and writing for history and scholarship.

There it — is a skill. It is training. It is specific. And I leaned in her —I leaned into her PhD, okay. And she, she coached me to do the type of research that the thesis was built upon. That this thesis is the thing — you would think no one else has written on this, but this thesis is the thesis that keeps giving.

And it was the command of the scholarship and the footnotes at that time. And the way that it was put together as a piece of scholarship in perpetuity. All right. That brought me to the table of formalizing what I had seen in the Mid-Atlantic, and I analyzed it. I knew exactly what Etan was asking me. I knew exactly what the problem was. I called my academic coach and I said, I gotta write my way through this degree or Pratt’s not let me out of this. I’m not designing a thing to get out of this or get through it or to graduate or anything. And I said, I said help, help me, help me to do the scholarship that’s necessary to write this document.

And she sent me on a path of research that had really never been documented before. And when I finished, I realized that the work was profound. And I realized that what Etan had asked me to do, I had accomplished and then some. It haunted me and I had no idea that print had — Print NCA had done any of this tracking of our community in the early sixties. There was just no way; there was no Google. There was nothing to search to know of Dorothy Hayes to know of this problem, to know anything. All I know is that I jumped on the path with a piece of research and a piece of scholarship and footnotes.

And I had no idea that Print had a history since 1968 of publishing our concern. I had no idea. All I know is that I was haunted with this document, and g graduated running the firm, and I was actually teaching at FIT and doing the designer thing, and this, this, you know, I’m, I’m, I’m, I’m doing this New York thing.

I’m doing it. I don’t know about it by the grace of God; I’m doing it. And this thesis is on the shelf is haunting me because it’s profound, and it needed to get out of my office. Nigel, it needed to get out of my office into the airways. I didn’t want anyone —I didn’t want to see any more suffering of what I had captured in this scholarship.

I get it. I took it, a yellow sticky, you know, I tease you about your yellow stickies. I took a yellow sticky. I put it right on the thesis, and I opened up my Print Magazine. This is — I used to be, you know, they used to come every month. I had a stack of them, and the office was close enough for me to walk from my studio.

And I wrote a note, Mr. Fox was the publisher. I said, Mr. Fox, my name is Cheryl Miller. I would like to make my thesis a magazine.

And I put it in a manila envelope. I dropped it off at the front desk of Print Magazine. And by the time I got back to my office, literally, I walked back into my office and the phone rang and it was, it was Mr. Fox. And said, Cheryl, this is Martin Fox. We want —it was real simple. This is —we want to make your, your thesis, a feature magazine article. I want to give you an hour —I’m going to give you an editor and I want to give you a contract. I want to give you a check.

And it was Tom Goss, my first editor, who gave me the best piece of advice. I — and just as the publishing of this last October 2020, I called him, and I thanked him. I said, Mr. Goss, I don’t know where life has taken you, but you gave me the best piece of advice, ever. See, I’ve never had a design mentor.

I had writing. I sh — I could have gone —I could have gone to Wellesley, okay. Well, I’m a writer, okay. And I got trained along the way. I had writing coaches; then, I got trained in scholarship. All right. And history making and making scholarship. I got drained. Okay. So, along the way, it all caught up with itself, but no design help ever.

But I had great editors and I had Leslie, Dr. King, and I had, I had writing even, even Nigel, even in my high school, my high school yearbook, you know, where, you know, you get inscriptions from your friends and your teachers. It wasn’t my art teacher who wrote anything. My English teachers wrote, if you don’t — you know, if you ever want to be a writer, find me. I’m like, why didn’t —I talk to my husband about this all the time.

So why then —why didn’t the English teachers jump in the pathway and tell me I was a writer? And we were in high school together. He said, Cheryl, everyone knew you wanted to go to art school. So, they didn’t get in your way. I’m like, okay. So, so I’m a trained writer because I’m a writer. And that’s where I got my help.

I’ve had great editors. And Tom said to me — he gave me the best piece of advice ever. And I give it on every interview. He said to me, Cheryl, you are a really good designer. The fact that you’re in New York means that you’re a good designer. He says, but that’s what —that’s not necessarily what you’re going to be known for.

I looked at him. I’m sorry, what? That’s what we’re here for in New York. Be a famous designer, I mean. Everybody in New York wants to be famous. That’s not what you’re about. Yes, you’re a good designer. You wouldn’t be here if you weren’t. He says this advocacy is your legacy. You stay right here with what you believe we should know. He said, stay right here. Don’t —don’t change. Don’t move to the left. Don’t move to the right. This is your advocacy. This is your legacy.

Nigel: Was this advice on the — as you’re preparing the Print piece or…

Cheryl: ‘87, 1987.

Nigel: Okay, so that’s the Print piece. So, 1985 is when you grew up.

Cheryl: My first editor told me, this is going to be it, lady. Don’t change course. And he was right.

Nigel: So, 1985 was the thesis and its title was Transcending the Problems of Black Designers…

Cheryl: No.

Nigel: To Black…

Cheryl: Yeah. Transcending the Problem on the Black Designer to Success in the Marketplace. And you can get that if you go to my Wikipedia or you just Google it. It’s in the Stanford University repository, you can see it. Nigel: Yup, and then the Print Magazine piece became Black Designers Missing in Action, 1987?

And then — then I’ll never forget how we got the chance to write again is the editor or associate editor from that called me up for a quote for Black History Month. And I started laughing. This was 2016.

Nigel: Okay.

Cheryl: I’ll never forget it. She must have thought it was crazy. I said you’re calling me for a quote for Black History Month. I was laughing just like this. I said —

Nigel: Okay, why are you laughing?

Cheryl: Because years have passed, we’re still working on this same issue. Everyone’s still looking for where’s the Black designer, right.

Nigel: Right, almost 30 years later. Yeah.

Cheryl: You know, unearth me for a quote. And I started laughing and I’m like, I have given you one of the most legacy articles that has no —it has an indefinite shelf life. I said, name me one other article that Print has published that lives on an in perpetuity. I said, don’t you

Nigel: Oh, as opposed to a quote? Let’s do a piece, yeah.

Cheryl: I said, let me do a 30-year reflection. Let me go back and see where everybody is. Let me go back and give a new state of the union. And if she didn’t go back and come back with the same thing, Martin facts that — Fox said to me in 1985. Mrs. Miller, we’re going to give you a contract, we’re going to give you an editor, and Black designers still missing in action. I do it like that, “still missing in action!” Was part of 2016.

Nigel: And what is it, what does it say to you? If 1987 is the first one, 2016 is the next one. And, and you laughed when they came back to you because they wanted a, you know, a superficial quote. A quote would, which really seems to downplay the import of both the message and the scholarship behind it and the impact of society.

Nigel: So, you know, what do you think that says, what do you think it says about society or the design profession?

Cheryl: No, it says about design present for — the design profession. You know, it’s such a clique and elitist thing. Don’t make me go there, okay? I’ve got some —I’ve got some connect the dots that I’m working on with two, two lectures. See, I’ve decolonized the 15 basic lectures that you would study for a semester. The history of graphic design. I’ve decolonized each one, all right. And I’m telling you, I got to, I’ve got a — I’m working on — I’m coming around the bend, okay. The spring then, okay. And coming around means I’m hitting —I’m hitting the New York School. I’m hitting the era of pushpin. I’m, I’m hitting psychedelic. I’m closing out. Okay, I’m closing out the lectures because the lectures take you all the way from Egypt and cuneiform. And I always tell folks don’t be, don’t be shocked. Egypt is in Africa. So Black graphic design starts in Africa, okay. And then somewhere you all get lost.

Cheryl: So, it starts there, yeah. That’s when my LinkedIn zingers. You know, last time I looked, when we talk about cuneiform and the writing, and that’s Egypt, then guess what? Last time I looked that’s North Africa — in Africa, okay.

Nigel: And let’s — let’s not —let’s not forget your LinkedIn zingers are legendary at this point. You have absolutely mastered that channel and that medium. If anybody wants to know what’s on your mind, we don’t have to, we don’t have to look far. We just check, check in on — and also IG you, you let it, you let it flow right there too. I like it.

Cheryl: Well, you know what it is? It’s revisionist and decolonizing history, the truthful notes. I’m just telling you the truth. I — Ida Wells well says, “you want to correct this, just tell the truth.” And so that’s all I’m doing, you know, and I open up with that. I lived through the history. I’m young enough to remember it.

And so, I was going to tell you until I get to glory, you know, this is, this is the truth. We wouldn’t; we wouldn’t be with IBM if I didn’t — right now, you and I would not be having this conversation if I did not tell you the truth about what Chris, what Chris — if I didn’t give you my IBM story and which was truthful, we wouldn’t be here.

Nigel: I love your use of language. And as a writer, you, you use language as, as a medium and, and, and so I’d love for you to help us understand this phrase. It’s so strong and it means so much to me and I, and I hope it means as much to others as well. Decolonize. Decolonizing, the history of graphic design and, and you’ve pulled together multiple themes in there before of technology and of imagery and of inheritance and, and, and so, so much to cover, but just, what is your sort of animating idea underneath this word? Decolonize.

Cheryl: What it means is to tell —so not for me, it means to tell synoptic stories around our history, around the cannon, which is, you know European, Anglo, and white. All right. And I just posted a lecture on my YouTube that discusses how. it’s called Hidden Truth. And I gave a lecture from Roger Williams University, and I explained exactly how I take the cannon and I decolonize. I will decolonize every piece of graphic design history because it only has one lens.

So, for me, it’s, it’s, it’s it’s a scholarship. It’s a technique that I learned in, in studying theology. To, to develop a synoptic view. And the synoptic view is — let’s take — let’s take an event, the capitol insurrection. Synoptic view is BBC report it, Fox news reports it, CNN reports it, CBS reports it, NBC reports it, all right. Everybody’s looking at the same event and your synoptic view — like my husband always says, let’s listen to BBC, and I’m like why are we doing that? He says, you gotta hear what Europe is saying about us. And it’s the truth. So synoptic is looking around a lens. It’s not parallel. Parallel is side by side, you know, kind of two of a kind, like twins. We’re marked parallel.

No, synoptic is we’re looking at the same event from intentional, from an unintentionally different perspective and lens and reporting what you see. So, for me, everything that the industry wants to present to me, it only shows me one view. So, you can take anything that’s going on, all right. And I’m like, okay, well, let’s, let’s, let’s get up and move around the other side of the table and sit and look from that view. You know what’s synoptic? You have a kitchen table, you have your family, you have your kids, you probably sit in the same seat every day. Breakfast, breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Tonight — yeah. Your kid, your wife —same seat every night. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I dare you to go home and say, everybody, we’re going to rotate.

Nigel: yep, yep, yep. It will throw everyone off. And I think that’s the point you’re getting at is that you’ve got some intention around throwing off the cannon and you know, that, that inertia, the disrupting of the inertia that you’re doing by doing that. Doesn’t it disrupt the holders of that mostly White cannon?

Cheryl: …Or everybody wants to hear from me, and that’s what’s going on. Nigel: What classes are you teaching now or just list of institutions? There’s too many to keep up with.

Well, listen —

Nigel: Tell us, what schools now?

Cheryl: I’m grateful that I’m closing. I’m posting grades. Oh my gosh. I am been at Roger Williams University. I’ve been at Lesley Art and Design. I’m with University of Texas Austin Design, and I’m at Howard University. And so, these four — two of them I’m teaching, two of them I’ve been teaching this, the decolonized cannon, and two I’ve been doing senior — senior design capstone thesis, presentation kind of work.

And then I’ve been invited because of Zoom in this platform. I’ve done jury work. So, I’ve done lectures at, I would say, I, I lecture two to three times extra a week and critic jury visits. I mean, I’ve been able to do —I had to chuckle at your quotes. When we started —

Nigel: Yes.

Cheryl: The minute we went into shelter, man, I raised my hands and said, hallelujah! I called a personal sabbatical. I said, oh, thank God. I don’t have to go anywhere, do anything, meet any schedule. The world has stopped.

Nigel: Oh, you mean last spring in 2020? The, the pandemic in the quarantine? Yes. So, the world’s slowed down and that allowed you to…

Cheryl: I used it as opportunity. Opportunity. Success is when opportunity that needs to prepare it. I went to —I went to work immediately. Immediately, I called the sabbatical. So, with that said, I’ve done all this work.

Nigel: Yes. Does the idea of the decolonize — we know that it is very clearly an intentional and important reference to the, the, the White European history that very clearly subjugated everybody it came up against while it colonized the world, essentially. Now, does it also in your worldview include the gender question and you’ve hit, you’ve hinted at it a few times, you know, only four or five and a group of 49 of the early Black artists in New York City.

And it’s not lost on me that you don’t wear that on your sleeve a ton. You know, you’re very clear about the decolonization and the ethnic issues that are important to you and your work and what in the legacy you’re leaving. Does — how, how do you see the gender question and how does that come to life in your, in your work?

Cheryl: Well first off, I found an explanation for the missing female component. I wasn’t looking for it, but I found it, all right. And if you go to my last article fourth, the fourth, or part four of my last article, there are notes there. Footnotes that authenticate my scholarship, that the first Black graphic designer is the slave artisan right off the boat from Africa.

I, I, you know, and a lot of that research was found in writings vintage documents and vintage— I found vintage Union meeting transcriptions and letters from the Type Union and the Printers Union meetings, notes. And we’re talking about meeting after emancipation, meetings. So, minutes, minutes, and page after page of what are we going to do with the slaves and the White men wanting the Black men to go back into slavery because now they’re competition and they’re afraid of now, what was the slave is labor and competing.

And there’s the core of your systemic practice, your racist practices, and White supremacy. The Trades wanted the Black men to go back into slavery. When I found those footnotes, I’m like, oh my gosh, I’m sitting here reading minutes, 19th century minutes from Typographic Union and the Printers Union talking about what are we going to do with these Negroes?

What are the — can they — can’t we put them back as slaves or slavery?

Nigel: Oh, my goodness.

Cheryl: Oh yeah. Look and Print let me publish the footnotes — you can find —and these are in vintage books and archives and documents. To answer your question, those same documents, they discussed the women right before they talk about the slaves. So, so the discussion is, are we going to give the membership? Are we going to give them cards?

Are we going to —membership cards? Are we going to, you know, this is a problem. Fred— Frederick Douglas had a son who tried to get into labor union — get in the Union in Washington, D.C. He worked for the treasury, okay, and they never ruled on him. They didn’t know what to do with him, all right. They wouldn’t give Union cards.

They wouldn’t give him membership. Yeah, there was a recorded — he was, he was a Pressman. And these stories and these notes— Union notes! I’m sitting here like I’m sitting right in the meeting; I’m reading. And before they start talking about the Black man and the slaves being competition and the White men being afraid of them, they dismissed the discussion with the women.

No women. Next! What’s the next topic? Dismissed. No women. And some even — I think I have one footnote that says they even vowed no women. And if there were, if there are any women, you know, through colonial America one or two, one in Boston, one in Virginia, I can’t call the names. Don’t quote me, you know?

And, and when I say don’t quote me, it’s off the record, unless I had my footnotes right in front of me. The oral tradition to my scholarship, there were two women who inherited presses from their husbands, okay. That’s the only reason why they were Press women. So, the women are — they weren’t even given a foothold. The slave got more consideration than a woman —than women, okay. So that begins, that begins the pathology of the issue of women in the business. It starts, it starts right there. Emancipation, what are we going to do with the slaves? And, oh, by the way, we’re going to do about these women? And starts with no women. And we’re going to argue over the slaves. Can’t we, can we, can we take them back? Can’t they go back to slavery.

Nigel: And I’m reading from your work there. And listeners can, can look this up. Print Magazine part four, and, and you write the fear of Caucasians losing opportunities is that the core of White supremacy. How many jobs could a White artisan potentially lose if the Negro artists and seize the opportunity first? What’s, what’s hilarious and in a sad way, is it at the time — I don’t know the census numbers at that time, you know, but right now White folks are, you know 75% or so of our U.S. population. You know, and the Negro or the, the Black American is only 13% right now. So, like, what are we really saying? And we’re, are we really —you know what I mean?

Cheryl: It’s like, they’re scared of the idea of losing the opportunities, but their privilege guarantees they’re not literally going to lose their opportunities, opportunities. And that’s even today, in my opinion.

Like, I always thought, it’s our DNA, you know? And I always use my favorite words, you know, it’s, it’s the pathology of the whole situation. And I’m so satisfied that I found the core. It’s kind of like cancer, cancer. We can’t get rid of cancer. Oh well, you don’t know where the tumor is. So, I hear everybody white supremacy, white supremacy, you know, systemic racism.

So systemic racism. I’m like, okay, where, where, where, where? Here it is right here. Right after slavery. Right, right here is the threat. Emancipation error, right?

Nigel: And I know you’ve heard this because I hear it as well. That was so long ago. Like we, we should, we should find a way to, to find those bootstraps we’re always told about. And there’s a, there’s an idea that we ought to move on, and the world is different. And by the way, you know, they, they didn’t own any, you know — I’m a White middle-aged man. I didn’t own any slaves anyway. So, you know, it’s not me.

Cheryl: We’re in a 50-year cycle repeating history that really, we can change. We don’t have to repeat this. And I think that the more truth and more light that’s put to, you know, so much of what we’re facing, okay. We’re, we’re in the season of the iPhone, it’s nothing but light onto the situation.

Nigel: You said a lot right there. Let me, let me, let me say, let me repeat it for myself, at least what you just —you just dropped something. “We’re in a 50-year cycle.” So, you’re saying from a civil rights era to today’s era, we’re revisiting some of the same exact race relation, social justice issues that were visited back then.

And we’re doing it again right now in— 2021 is where we are as of this recording, but it’s been happening for a while, most notably, maybe 2016. And, and so —I mean, what goes through your heart in that moment? Because you, you, you’re an interesting — you’ve got that such a rich perspective, Ms. Cheryl, because you are before civil rights, you’re during it, you’re after it. And now you’re in this 2016 to 2021 space. What goes through your heart when you see that the world has to deal with this still?

Cheryl: Well, first off you can’t— I can’t worry about all of it. I can only wor —I can only worry. I worry, and I’m empathetic about all of it, and I, and I work. I’m telling everybody adopt the spot. I work in the spot of the garden, where I, where I belong. Okay, and so where that is, is design justice.

Nigel: Design justice, okay.

Cheryl: Which is different of my work, which was diversity, and equality, and inclusion. I pivoted, I’m now onto design justice, and diversity, and equity. I grew through a season when things became equal. Now, I’m looking at equity, and so my work continues with a pivot. I can’t — my, my protest is telling the truth, and I’m still doing this work. This is my station. I’m at my station. I have not changed, and I have not been arranged —rearranged. I’m why — I’m doing with Tom Goss told me to do. He says, “stay right there.” I’m still —I’m in the same place. Pivoting, knowing I’m in a 50-year cycle, and then I’m telling everyone that I know.

And especially at our conference and IBM, et cetera. I shared with you at the beginning of this. You asked me about RISD, and I shared with you that all the Ivy leagues schools came down looking for students. They were opening up. 50-years. We’re in a season of reparation and I don’t know how long the season is going to be. What success is when opportunity meets the prepared.

IBM has been hiring. I look on LinkedIn, I never seen so many folks of color. Their chief officer this, designer this, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. There’s a season of reparation. I cannot tell you how long the season is open.

Nigel: Design justice. And if you hadn’t —it’s not lost on me that, you know, you, you and I did not compare notes ahead of time. I, I make a point not to try to script out these conversations, and it’s not lost on me that that editor would not have made or given that advice. If, if you didn’t take it upon yourself to have the strength, honestly, the courage maybe is a better word to walk down to the office of the publisher and pass them your thesis. And it was exactly what Madam C.J. Walker said, don’t sit down and wait—”

Cheryl: I’m honored.

Nigel: I’m really excited about, I’m sorry to cut you off, but I just wanted to put a capstone on that idea. It’s the quality of the practitioner spoke for you when you weren’t there. And it was your stand in. And because you are in, and were top talent in that moment, the opportunity came for you to get published again on that piece.

But if so, sorry about it. I just want to make sure that the idea was rattling around in my brain. Thank you for letting me get that out.

Cheryl: Well, I appreciate that, and I want to give you some — I want to submit something to you, humbly. You’re, you’re beyond accurate because in this shelter in, I said,

Nigel: Get up and make them. And, and so, yeah, I didn’t know that you’re going to tell that story, but it’s not just a metaphor. You literally didn’t sit down, you stood up and walked down the street to the publisher’s office and, and gave them your work, and what I love — and then another piece that I love about that is that the quality of the work spoke for itself as well. You, you — that wasn’t a handout to you. You didn’t get published because of a quota, you know, that someone had to meet, you got published — I mean, the thesis was published, but then you got published a second time in Print Magazine in ‘87 because they, because they read it, and they knew what was in it was true.

Cheryl: I query Print and I said, I want to write one more time and I’m going to put it into it. So, a part of my shelter in sabbatical is I want to find where is the Black designer? I want to be done with this.

This is, this is, this is worrying me. And I, I asked to write again. They contracted me for 1500 words, they paid me for 1500 words. They gave me— Zach was my editor, it’s the second time — he’s my second editor. The second time I’ve written for him. He wrote me. He said, Cheryl, you submitted 14,000 words. We have never published an article this long.

I said —listen. And he said to me, we’re going to leave it alone. We’re going to break it up into four parts. Print Magazine allowed me to write unencumbered.

And Zach wrote me. He said on several occasions; I keep them. I might frame them, okay. He said this is so good. One email was so, so, so good — four so’s. I’ve never had an editor, art director, anybody give me kudos like Zach at Print Magazine. He said — then he wrote me another —this is historic. This is iconic.

And then on top of it, which is what editors and publishers have to do. We made sure that my footnotes were my footnotes, the fact-checking, okay. And so, one of the things that, you know, one of the things I pride myself on is whether it’s design work or the writing or whatever I do, it all ends with the same— it all ends with the same quote that I live for myself, okay.

I tell everybody the same thing and I tell everybody the same thing and I live by it. Let me, let me see if I can get the quote, okay. It’s at the end— it’s at the end of my thesis. It’s at the end of, at the end of all my articles. And you would think, I would —see, you, you memorized yours, you would think I had it memorized. But indeed, it’s that the end of everyone— let’s see one 36. Tracy Hills: I chuckled. He said auntie— he calls me auntie. He said, “I got you, I got your Print Magazine. Next time I see where you sign it. I got it on eBay for $60 bucks.” I said, you got to be kidding.

Nigel: “I have learned that success is to be measured, not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he or she has overcome while trying to succeed. Looked at from that standpoint, I almost reached the conclusion that often the Negro boy’s and girl’s birth and connection with an unpopular race is an advantage, so far as real life is concerned. With few exceptions, the Negro youth must work harder and must perform his or her task even better than a white youth in order to secure recognition. But out of the hard and unusual struggle through which he or she has compelled to pass, he or she gets a strength, a confidence that one misses whose pathway is comparatively smooth by reason of birth and race.” That’s from ‘Up from Slavery’ by Booker T. Washington.

Cheryl: I live by it, and, and all my writings in the same way. I lived by it, I targeted, and I said, okay, I gotta be better. I gotta run faster than the best White boy.

Nigel: Right.

Cheryl: And I don’t know what could take me back. Woman, being mixed, being Black, being outside of the norm. I don’t know. All I know is I’ve got to run faster, and I’ve been, I’ve been running in this excellence the whole way. And, and now I’ll be honest. I clocked 50-years at this because I started this path when I was a teen. I jumped on the path of having to fight my —you know, there’s other interviews. My, my, my high school wouldn’t send my transcript to RISD and, you know, my art teacher told me I’d never be an artist. I mean, I started fighting this drama when I was 17.

Got to RISD, first day, all of us were there and the admissions person who greeted us said, “well, half of y’all, aren’t gonna make it.” I’m like, oh, well, welcome to RISD. I’ve been at this a while. And so where, where I am now is I’m not having — this legacy has proceeded me. And I’m being in —graciously being invited and that’s new for me. I’m being invited to the table conversation in different, in different venues. And so, the 50-years of labor; I’m being, I’m being rewarded.

Nigel: And I love that. And, and, and you know, these three volumes of Print Magazine’s publication of your work which can be found at printmag.com. Cheryl Dean Merrill —Miller sort of show this three-act play: missing an action; still missing in action, 30 years later; and then five years later, forward in action, which I think is a great title for that third piece and not just title, but a greeting.

I look for inspiration, Ms. Cheryl, it’s just, what sort of moves me through the world is that I moved from something that inspires me to the next thing to the next thing. I’m always trying to find that, that, you know, something that, that sparks me if you will. And so that idea of forward is to me, at least is so important.

It’s something I try to teach my children and my wife, and I believe in it. What would you do if you were queen for a day? We’re going into hypothetical space there for just a second. You had the magic wand. That might be another way to think about it. And in this magic wand is the power to bring forward an action, an activity, a decision, a new reality in whatever way you want it to be in the, in the, in the auspices of forward and action. What, what would that, what would be that magic stroke that you’d have happen?

Cheryl: First off, forward, and action is a warning to the oppressor. I’m going to come back and answer, but I want to tell you about this article, it’s a warning to the oppressor.

If you notice something I wrote in 2016 and I wrote in 2020. What’s — how many years is that?

Nigel: It’s four years, 16 and 20.

Cheryl: Okay. From 2000 —from 1987 to 2016, is how many years?

Nigel: 29 years, almost 30.

Cheryl: Within four years, I gave a different report. In 30 years, I saw no different — no difference. In four years, I’ve served notice.

Nigel: I see.

Cheryl: I don’t know whether in those four years folks graduated folks, you know, stuff shifted. There is a new practitioner that I’m reporting on in —within a four-year period of time. And I’m serving notice. And when people ask me, what’s my closing word, I said, “compete, you’ll win.”

Because the — because we’re fierce. It’s like there was, there was a — there was an anecdote in, in, in my, in my draft that we didn’t include. It comes from, it comes from the first chapter of Exodus as a new Pharaoh in town. And he’s, he, he does not want to have relationship with the Hebrews, and he makes it, he makes it worse.

He’s the oppressor, and the Hebrews multiplying and grow stronger. This situation has backed this community up for decades to the point where it has multiplied itself to be fierce reckoning, forced to reckon with. I’ve never seen so many PhDs of scholarship. I don’t even know what folks are talking about. I’m like, alright, you backed us up now what? Okay. Some of these some of these tech jobs — I saw something today. I’m like, I don’t even know what it is. I’m not even going to play like — Cheryl, Cheryl knows a lot. She doesn’t know this, but whatever I do know is that brothers got that, and you don’t. There is a force for reckon with.

Nigel: Right.

Cheryl: We don’t play, Nigel. We don’t, we, I told you I stay in my lane. I’m a history, and I remember things you should know. That’s it. I don’t —okay. Some of this stuff I’m like, oh no, oh no. So, you oppress this comm — back this community up so badly, that now it is multiplied. It is fierce. It’s fierce.

Nigel: I see the metaphor. You backed them up, so it’s — you know, so many people through the centuries, honestly, but, but especially over the last several decades, weren’t prevented from the practice of design based on the melanin in their skin. Right, and so, because you back that up because the oppressor back that up, there’s built up pressure. Cheryl: Yes, now you look at what you created. All right, look what you forced to birth. Okay, you can’t compete with these Black designers. I’m sorry.

And that’s where your idea of equity comes in because equity says different than equality. Equality is everyone’s equal right now, and everybody gets the same treatment right now. But what equity says is the starting line was 50 yards behind the White folks for many of us. Well, for all of us, that, that, that are Brown skin and Black skin.

And so, because the starting line, we might be running at the same speed, but we’ll stay 50 yards behind unless there’s some equitable changes that take place. And so that’s that pressure release. I’m just trying to extend the metaphor a bit, but that’s the pressure release. I think you might be talking.

Cheryl: So, what I’m encouraging people — you better compete. This is seasonal reparation and your part — you’re faster and smarter than everybody who’s been out here. Who’s had a White privilege and it’s been cushy. May the best person win. And so forward, and the fact I wrote in four years, I saw — I’ve seen a shift. I’m like all you all back, everybody up here. Now look at this, look at this.

Nigel: That’s powerful. That’s powerful. And everybody knows anything under pressure. When it, when it, when it finally gets let loose or there’s a fissure or a crack, it, it, it explodes forward. Right? So that’s what, that’s what we’re seeing from a 30-year interim to a four-year interim of the amount of time between your writings, those are the observations.

That’s what you were feeling and seeing in the industry. Nothing changed for 30. And now we’re seeing forward in action in the four years since then. And, and even in the one year since that writing the, the activity has continued. So that’s where the forward movement is. And I love how you’re ending this, this, this conversation on this idea of excellence, right?

Is that there’s never an excuse for not being excellent. We’re not saying that, right. We’re not saying handouts are the way to go. We’re not saying that quotas, just because of the way to go. What we’re saying is what’s — go ahead.

Cheryl: You have to be excellent, more than excellent. So yeah, there’s no resting on it. And this is, this is the season to compete. You’ll win. So, in that article, I’m saying, look, here’s your truth. They’re scared of you. So, and now go, go get it.

Nigel: Go get it. Go get it. Just like you put — you dropped off your thesis, just like you, you landed on Ivy league campus at RISD. Just like you are, are continually uncovering more research, whether it was the genealogy studies that you, you talked about at the top. The quality has always been your measure.

And, and if, if a mentee came to you and said, what’s the secret? I would almost — can anticipate your answer. There is no secret. Go compete. Right, do the work because now it’s time.

Cheryl: Look here’s one for you. Everybody wants me to have a mentor. Who was your mentor? I’m like, I don’t have one, no. Serena Williams, Serena Williams, a British Sportscaster — you can find it on YouTube, all right. She goes to Compton, and she interviews Williams and his two little girls. Venus is 13 and Serena is 11, and she looks at Serena and — you know, they’re, they’re in the little white and their little beads and everything, you know, it all the way back.

Nigel: I remember that.

Cheryl: And she looks at Serena and says, “so who do you want to be like when you grow up?” Like thinking, she’s going to say Billie Jean King or something like that. She looks right in the camera without hesitation. You can Google it. She looks right in the camera, and she says, “they’re gonna want to be like me.”

Nigel: Wow, such confidence. I love that. And look where we are. People do want to be like her. She’s still on TV making commercials and still being a model.

Cheryl: It’s just knowing. It’s just knowing what I call your, your, your right, your, your first brand recognition gifts. Which means you’re the only one with it. Yeah, you’re, you’re the first one with it. And the only one with. And you’ve been bre — like Tracy Hills is one of my — Mike Nichols. I’ve got a few — their brand name recognition first, first out. Trey, Trey will always — I love him. He always calls me auntie, and he’ll tell you, his story. That he came with an idea, and I said to make typefaces out of civil rights posters with lettering. And I said, “Trey if you don’t do it, somebody else will.” So let somebody come along now and try to do that. And what no —he’s in a space all by himself.

Don’t duplicate. Create! There’s enough, there’s enough within us. Okay, you want to be in that spot— like here, you want to be, you want to be in this spot.

Like you go, you go, you go to FedEx, and you say, “can I have 10 Xerox’s please?” And they’re candy machines in the back. You want to be in the spot — you go to McDonald’s, “can I have a tall Coke please?” And all we have is Pepsi in the back. Can I, can I have a Kleenex please? And the box says Cottonelle. You want to, you want to be in the first spot, the only spot first brand recognition.

And we all have that giftedness. If we will listen and be brave enough to use the gift of God that’s been given us. And that’s it.

Create. Don’t duplicate. Create. Design thinking on a yellow sticky. Are you still with me?